China’s cultural revolution

I have adapted this balanced account of the Chinese Communists Party’s (CCP) treatment of the Cultural Revolution from one published in DW News. Readers can judge for themselves how official views have changed over the years. In addition, the article mentions a museum that never happened. However, such a museum did exist at one time but has now closed, as you will see below.

The event

On May 16, 1966, China began the disaster of the Cultural Revolution. The decade-long Cultural Revolution caused indelible trauma to the Chinese nation. Millions took part in this vortex of history and politics, unable to escape. This history is still a very sensitive topic in China.

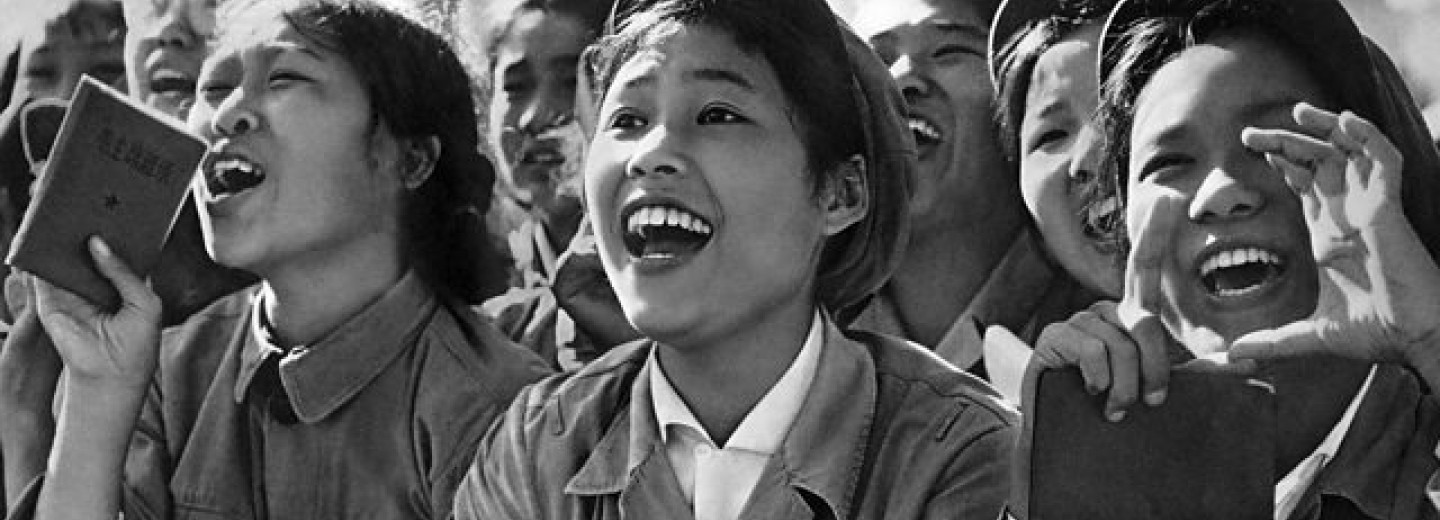

On November 26, 1966, at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, Mao Zedong inspected the Red Guards for the eighth time.

Criticising the Cultural Revolution

In 1978, the reformists of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Deng Xiaoping, spent more than three years initiating a ‘discussion on the standard of truth’. In 1981, they widely criticised the Cultural Revolution. Their resolution stated that the Cultural Revolution was a civil turmoil that brought serious disasters to the party, the country, and the people of all ethnic groups. Mao Zedong made serious mistakes in launching and leading the Cultural Revolution.

Immediately after this statement was issued, Hu Yaobang said that the serious mistakes of the Cultural Revolution could not be corrected for a long time. This was because it brought about the destruction of the CCP’s normal political life and democratic centralism. In particular, the collective leadership of the central government was undermined.

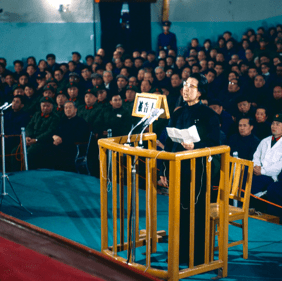

From November 20, 1980 to January 25, 1981, the CCP held a public trial against 10 defendants of the Gang of Four and Lin Biao Group. In the photo Mao Zedong’s widow, Jiang Qing, is defending herself. (Visual China)

After this came more reflection. In 1982, Hu Yaobang again pointed out that the Cultural Revolution had a profound impact and caused serious harm. “Whether you have the courage to conduct self-criticism about mistakes, and whether you can conduct such self-criticism historically and correctly is the only way to reduce the chaos.”

In 1987, Zhao Ziyang’s report linked the reform of the political system with the prevention of a recurrence of the Cultural Revolution. The report proposed that reforms should be adopted to move democratic politics step by step towards institutionalization and legalization. This would be the principle guarantee to prevent the Cultural Revolution from recurring and to achieve long-term stability in the country.

The Cultural Revolution has since become a forbidden topic for discussion.

Strict censorship

As the Cultural Revolution was criticised in the 1980s, literature emerged that talked about the trauma of the Cultural Revolution and reflected on its history. Many texts touched on the connection between the Cultural Revolution and contemporary Chinese history. As a result, China has frequently banned certain cultural revolution-themed works.

In 1986, the Central Propaganda Department issued a notice insisting that, for papers that narrate the historical facts of the Cultural Revolution, “Nothing should be published without strict censorship.” If something has been published: “Do not post comments or messages”. In 1988, the Central Propaganda Department issued the “Regulations on the Issue of Cultural Revolutio Books”. Citing Deng Xiaoping’s spirit of unity and forward-looking, historical issues should be broad and not detailed.

As a result, writing about and researching the Cultural Revolution was strictly controlled and the space for discussion severely reduced. The history and memory of the Cultural Revolution became a forbidden study. This continues to this day.

Downplaying the Cultural Revolution

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, especially after the June 4th crackdown in Tiananmen Square, the disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the drastic changes in Eastern Europe, the CCP felt that the ideological crisis was serious. It was eager to develop a new political framework. In 1993, the 100th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth, China’s first large-scale commemoration of Mao Zedong since the Cultural Revolution, became an organized “Mao Zedong fest”.

The ruling party also began to “forget” the Cultural Revolution. China watchers noticed that, while the report of the 13th National Congress (1987) of the CCP mentioned the Cultural Revolution, none of the reports from the 14th to the 19th National Congress (2017) mentioned the Cultural Revolution.

In 1991, Jiang Zemin mentioned the Cultural Revolution at the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China. He said that the CCP “for a period, under the guidance of the “Left” ideology, has made some mistakes, especially serious setbacks such as the “Cultural Revolution.” In 2001, on the 80th anniversary of the founding of the party, Jiang Zemin reiterated that the CCP: “in some periods in history made mistakes and even encountered serious setbacks”. But he avoided talking about the Cultural Revolution. In his speech on the 90th anniversary of the founding of the party in 2011, Hu Jintao followed Jiang Zemin’s words and avoided talking about the Cultural Revolution.

2016 marked the 95th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China. In his speech, President Xi Jinping did not talk about the Cultural Revolution, nor did he mention that the CCP had made mistakes or encountered setbacks. This year, the CCP celebrated its centenary. The column “Reviewing the Party History” published by The People’s Daily, failed to mention the Cultural Revolution.

Remembering the Cultural Revolution

The DW News article refers to Ba Jin, then one of the most famous contemporary writers in China. “He wrote a masterpiece, ‘Caprice Records’, which deeply analysed the Cultural Revolution. To prevent such tragedies from repeating, he proposed the establishment of a Cultural Revolution Museum to allow future generations to remember this dark history. During his lifetime, Ba Jin kept appealing. Although his proposal was supported by many people of insight, the Cultural Revolution Museum has not yet been seen.”

In fact, the DW news is wrong. In an article in the Global Mail and News on July 22nd 2010, the writer describes how Shantou, in southern China, opened the only such museum in 2005. “Not many people come here,” acknowledged Peng Qian, the museum’s 78-year-old founder and volunteer curator. “Why? Because we’re not allowed to publicize ourselves and there’s no news allowed about it on television or radio either. There are even people living in Shantou who don’t know about us.”

“Between heaven and earth, such disastrous history only exists here,” reads the blue calligraphy running down one side of the grey concrete frame. The other side adds: “The most important thing in the world is the ability to judge what is right and wrong.”

Then, in 2016, a few weeks before the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, the New York Times reported that the museum was ‘closed for repair’. It has never reopened.

Workers arrived bearing concrete, propaganda banners and metal scaffolding. They smoothed concrete over the names of victims, wrapped “Socialist Core Values” banners around the main exhibition hall, placed red-and-yellow propaganda posters over stone memorials to the terror, and raised scaffolding around the statues of critics of Mao.

Redefining the Cultural Revolution

In the 21st century, China’s social transformation has come to a crossroads and political reforms have been shelved. Momentum for reform has been lost and consensus broken. The dispute between left and right has been fierce, and people’s differing opinions on the Cultural Revolution have further intensified.

We may never know the true darkness of the Cultural Revolution. Official denials and literary narratives of the 1980s only scratched the surface. Many crimes, traumas, and sufferings were silenced and buried. They could not be expressed openly.

Some say that the Cultural Revolution has been demonized. It was an experiment in socialist democracy and freedom. Although it failed, its value still exists. The many contradictions caused by reform and opening up, such as an unfair society, the wealth gap, corruption, and moral decline, lead people to regard the Cultural Revolution with nostalgia. They see it as a remedy against wickedness.

Now China has entered the era of the Internet and globalization. Memories of the Cultural Revolution have spread through social media. Many memoirs, oral histories, biographies, and autobiographies of the Cultural Revolution have emerged. In addition, writers have published many articles about the history of the Cultural Revolution. Public memory of and reflection on the Cultural Revolution far exceeds that of the 1980s.

Perhaps the CCP is worried that public opinion is out of control. Its countermeasures are to “oppose historical nihilism” and “dare to glorify the ideological struggle.” ‘Negative’ articles and speeches were purged. Authors were punished for criticizing Mao Zedong and accused of violating party discipline.In addition, the CCP also proposed “two non-negatives”. The historical period after reform and opening up cannot be used to deny the historical period before reform and opening up: and the historical period before reform and opening up cannot be used to deny the historical period after reform and opening up. This attempt to bridge the gap between the left and the right was misunderstood by the outside world. The West saw it as an inability to deny the Cultural Revolution.

This caused much controversy.

At the same time, the government has also tried to position the Cultural Revolution as part of history. In 2018, a new history textbook played down the Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution is seen to be “Exploring the Road to Building Socialism”. The Cultural Revolution is no longer categorised as “turmoil” and “disaster”.

As I have commented many times in this blog, we must learn from history. As with Colonialism in the West, the Cultural Revolution is history from which the Chinese nation should learn. The CCP reformers of the 80’s realised this. However, although the Cultural Revolution ended 45 years ago, it is again a forbidden topic. Attempts to redefine it in recent years, show that China has not yet emerged from its shadow.

It is a hurdle that China needs to cross.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang