How did Hong Kong get here?

In last week’s post we discussed the Chinese Communist Party. This week we cover the background to Hong Kong’s status today. In order to understand what has happened and why, we must first understand Hong Kong’s history over the last 150 years.

Unpalatable as it is, the emergence of Hong Kong as a world city began with opium.

In the 18th century, the British demand for Chinese silk, porcelain, and tea created a trade imbalance between China and Britain. To pay for British needs, silver flowed out from Britain and into China through Canton (Guangzhou). To restore its cashflow balance, the British began to grow opium in India for British merchants to sell illegally in China. This reversed the Chinese trade surplus, drained its economy of silver, and vastly increased the number of opium addicts in the country. Understandably, this seriously worried China.

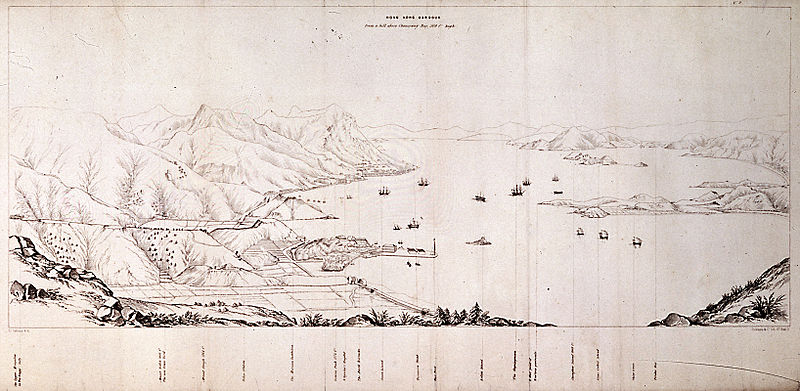

In 1839, China seized opium stocks in Canton to stop the opium trade. The British government backed the opium merchants. In the Opium War of 1839, the British navy defeated the Chinese with superior ships and weapons. In 1842, China was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanking – the first of the “unequal treaties” – which ceded Hong Kong Island to the British Empire. Defeat for China in a second Opium War, resulted in Kowloon being ceded to the British in 1860. China subsequently leased the New Territories to Britain for 99 years from 1898.

“We landed on Monday, the 25th of January 1841, at fifteen minutes past eight a.m., and being the bona fide first possessors, Her Majesty’s health was drunk with three cheers on Possession Mount”, claiming Hong Kong for the British Empire.

In 1841, the population of Hong Kong Island was about 7,450, mostly Tanka fishermen and Hakka charcoal burners, living in a number of coastal villages.

Fast forward

Between 1843 and 1997, Britain appointed 28 Governors to Hong Kong. The Governor was the head of the Colony’s Government. He (all were male) was the representative of the British Crown in the colony. Executive power was highly concentrated. The Governors appointed almost all members of the Legislative and Executive Councils and were President of both. The British government provided ‘oversight’ to the colonial government; the British Foreign Secretary approved any additions to the Legislative and Executive Councils. Democracy was not available to British colonies.

From the start, the British governed Hong Kong’s economy under positive non-interventionism. Some might call it laissez-faire. The colony quickly became a regional centre for financial and commercial services. By 1859 the Chinese community numbered over 85,000 supplemented by about 1600 foreigners. The economy was dominated by shipping, banking and trading companies. Industrial expansion in the nineteenth century included sugar refining, cement and ice factories, alongside smaller-scale local workshops.

Between the two world wars, Hong Kong was affected by chaotic events in Mainland China. However, the problems on the mainland also diverted businesses and entrepreneurs from Shanghai and other cities to the relative safety and stability of Hong Kong.

After the war-time Japanese occupation ended in 1945, Hong Kong’s economy quickly rebounded. The Colony was vital to the international economic links of the new People’s Republic of China (PRC). Hong Kong’s imports of food and water were a source of foreign exchange to the PRC and ensured Hong Kong’s usefulness to the mainland. In turn, cheap food from China helped to restrain rises in the cost of living in Hong Kong. This kept wages low during the period of labour-intensive industrialisation. Among many other specialities, Hong Kong developed a thriving movie industry that became the third largest in the world.

1984 – an Orwellian date?

China had always insisted that its lease of the New Territories to Britain would expire on 30th June 1997, with resumption of Chinese sovereignty. Although ceded to Britain forever, Hong Kong Island on its own could not be viable. In 1982 negotiations between Britain and China began in order to decide the basis on which the Colony would return to Chinese rule. In 1984, the two Governments signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration and agreed The Hong Kong Basic Law. China resumed sovereignty on 1st July 1997.

“One country, two systems” defined the basis of the agreements. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would continue to govern the rest of China under its own laws and practices. Hong Kong would become a Chinese Special Administrative Region (SAR) and continue its laws, customs and systems for at least the next 50 years. The PRC and its Hong Kong SAR are heavily co-dependent economically. The Colony seemed set for a smooth transition back to the Motherland.

What went wrong?

It is 40 years since negotiations about Hong Kong began and 24 years since China resumed sovereignty over Britain’s former Colony. Global and local conditions have changed in ways and to an extent that few could have foreseen. Among many others:

- In 1982, China ranked 10th largest in GDP in the world. Today it is 2nd largest

- In 1982, the global population was about 4.6 billion – with no internet. Today the population is about 7.9 billion people with almost instant access to each other

- Poverty in China has fallen from 88% in 1980 to under 1% today

- Poverty in Hong Kong has risen from around 12% in 1990 to over 20% today

- None of Hong Kong’s students were even born in 1997. Many of their parents were not born at the time the Joint Declaration was signed

- Hong Kong has become a global focus of the struggle between China and the western world

Perhaps most telling of all, is that many of Hong Kong’s senior civil servants joined under and were trained by the British. Carrie Lam, for example, the current Chief Executive of the Hong Kong SAR, joined the Civil service in 1980. Chief Secretary for Administration, John Lee, joined the Hong Kong Police in 1977. Secretary for the Civil Service, Patrick Nip, joined the Civil Service in 1986.

They are competent, reliable, experienced and efficient civil servants. But they may not have – and almost certainly, could not have – the skills to lead a complex city in the 21st century. In this respect they are similar to governments in many parts of the world. Among 230 significant protests around the world since 2019, over 75% have political causes. The governments concerned also struggle to respond effectively.

With hindsight, given all the above, there was bound to be a clash of ideologies between some groups in the Hong Kong SAR and Beijing. When such clashes occur, bickering about the meaning of words used in carefully phrased agreements made 40 years ago is inevitable – and pointless.

Moving forward

Let us assume, optimistically perhaps, that everyone involved wants the best for the people of Hong Kong. The most important thing for them is a strong economy. Without that, nothing is possible. Hong Kong’s problems – poverty, housing, health, social stability – all depend on having enough money and spending it effectively. A strong economy cannot exist in chaos.

Let us all, then, accept these facts:

- Hong Kong has always been Chinese and will remain Chinese. Independence in any form will not happen.

- Hong Kong and mainland China are, have always been, and will remain closely tied economically

- The CCP runs China in a different way from how western governments run their countries. Beijing gives Hong Kong considerable latitude because of its 150 years under British rule

- The Hong Kong government needs to be proactive in addressing the city’s problems. Positive non-interventionism is no longer enough.

- As a global financial centre, Hong Kong is of interest to the global community and will continue to attract comment that Beijing may not appreciate.

It is a cliché but so true. The business of Hong Kong is business. Business needs stability and calm. Hong Kong will continue to thrive and prosper, if we all accept that.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang