Isabella Bird’s journey on the Yangtze River. Part ii

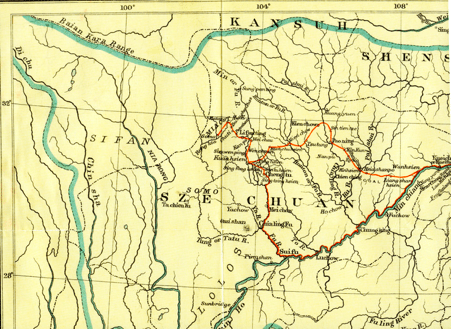

Last week we left Isabella Bird in Wan Hsien, now a district of Chongqing, to continue her journey by land. She used the map below as reference in her book. I include this map because I have found it hard to match some of the villages on Isabella’s route into Tibet with towns known today. I hope a kind reader may enlighten me!

Being keen to see the landscape and people of western Sichuan, Isabella decided to end her river journey at Wan Hsien and continue by land. She went ‘alone’ – i.e. without any Europeans. However, her host, a missionary, arranged for her to hire a sedan chair with “four chair bearers and six coolies”. The “comfortable chair also contained my camera and 40lbs (18 kg) of baggage together with my weight.”

Chair travelling is the easiest locomotion by land. My coolies did 27 miles in a day. Chair bearing is a trade by itself and bearers have to brought up to it.

In the pass of Shen-kia-chao, she noticed three criminals hanging in cages and was told they were to be starved to death. All had been robbers but ‘Chinese justice is retributive and takes little account for human life.”

In Liang-shan Hsien, Isabella faced a riot directed at her. She barricaded herself in her room at the inn, but the crowds screamed ‘beat her, kill her, burn her’ and used wooden beams to break down the door. She was saved by the authorities. Her landlady asked her afterwards, though:

If a foreign lady came to your country, you’d kill her, wouldn’t you?

She faced another riot at the next village “which delayed my dinner considerably. Wretched evening; riotous crowd; noises, too cold to sleep.”

In the coming days, she muses about the nature of Chinese society and education, this “being the only way by which a man, be he prince or peasant can obtain employment and honours. China is, in fact, the most democratic country in the world.”

On 21st March, in Paoningfu, Isabella bought, equipped, and opened a memorial hospital (as she also did in Kashmir) dedicated to her much-loved sister who had died a few years before.

In Mien Chow, “a hostile city”, she again stayed with missionaries. She was impressed by the hard life they lived and their resilience to frequent attacks and riots.

It is a grave question whether married men and women ought to be placed in regions of precarious security.

Isabella and her hosts left Mien-chow on 31st March, travelling ‘by infamous roads often not more than a few inches wide.” The photograph shows her host, an English missionary, ‘in his travelling clothes.”

Two days later, Isabella was again attacked by a large crowd. Stones were thrown in volleys; one hit her head and knocked her out. Taken to a local inn, the crowd battered at the door of her room being stopped only by the arrival of some soldiers. “

I felt very ill the next day…and suffered from brain disturbance (concussion surely) for several days…but why should I not go on”, Isabella continues, “and see Tibetans, yaks, rope bridges and colossal mountains?”

Kuan Hsien (Guan–xian) was famous in Isabella’s day for its trade with Tibet. This involved medicine of all kinds, musk (“selling for 18 times its weight in silver in Chungking”), rhubarb, and aconite. Greeted with “here is another child-eater” by crowds, Isabella was nonetheless impressed with the temple in honour of Li Ping.

Li Ping (or Bing) was a famous hydrologist in the Warring States period. in about 256 BCE, he designed and built an irrigation system to stop the area flooding each spring when the snow melted in the mountains. The system was still in use when Isabella visited but was destroyed by the earthquake in Sichuan in 2008. It has since been rebuilt.

In honour of Li Ping, the city renamed a temple (originally built for their king) that Isabella visited. Her photograph of the ceiling is alongside the temple as it looks today.

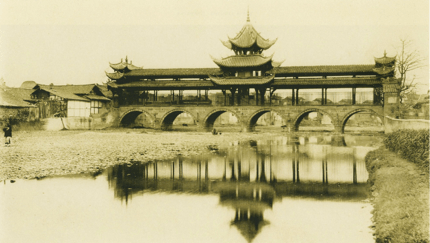

Four days later, Isabella reached Chengtu (Chengdu). The city had recently experienced major riots against foreigners. Isabella was impressed by the wide streets and bustling markets. She also enjoyed staying in the comfortable residences of the American missionaries. The Government allocated these as reparation for the damage done to American property in the riots.

She had already decided however, to see western Sichuan and travel to Somo (Suomo) along the Min river valley. In a two-week journey, she finally saw the famous ‘Tibetan’ rope bridges. The builders tied a strong bamboo rope between two rocks either side of a gorge. They then strapped themselves to semi-circles of bamboo and launched themselves, sliding along the rope until reaching the end of its dip.

To ‘climb’ to the other shore, they slowly dragged themselves, hand over hand, up the rope until they could step off safely.

Isabella’s journey continued with magnificent scenery, tiny paths, and fine, cool weather.

Most of the villages contain mysterious-looking square stone towers, sloping very gently from base to summit. They are built without mortar with huge blocks of stone.

She obtained varied explanations for their use and concluded they might have been watchtowers or places of refuge for the Man-Tze villagers.

(I had difficulty identifying the Man-Tze people. However former names for the Miao minority group in China were Miao-tse and Miao-tsze. Furthermore, Isabella’s map names the region through which she travelled as Miao Tze. It seems clear that the people to whom she refers as Man-Tze are, indeed, the Miao people.)

All along the lower waters of the Siao Ho, all the Man-Tze villages that have not been destroyed are now deserted…. These tribes are not Tibetan…but they remind me of some Tibetan tribes I have met.

Isabella found out what she could about the Miao.

They are all named ‘barbarians’ by the Chinese. But they divide themselves into many tribes. The headman of each tribe is appointed directly by the Emperor of China and for life. Among the noteworthy characteristics of the Man-Tze is the position of women. They are not only equal to men but do everything together. Their standard of morality is low.

Their views are narrow, their ideas conservative and their knowledge barely elementary. They know of China, have heard of Russia but never of Britain. The characteristics of the Man-tze face is European in feature and expression and recalls the Latin races. Their ornaments are beautiful and of fine workmanship. When I asked by whom they were made, they invariably replied ‘by the Arabs’.

(Isabella observes the friction between the Chinese and the Miao. In fact, for centuries there had been fighting. The Miao objected to their perceived absorption by China and rebelled many times. The last and most serious rebellion had taken place a few years before Isabella’s visit: this explains the damaged and deserted villages she saw. Many Miao families migrated to nearby countries – and even further afield – after their most recent defeat.)

After visiting the splendid castle at Somo (Suomo), Isabella set off for the journey back to Shanghai via Chengtu and Chunking again. The villagers refused to sell the party food at one point. They would have starved except for gifts on their journey down the River Fu.

At Luchow (Luzhou) Isabella was impressed by the ancient Bao’en pagoda. Built in 1148, it was restored in the 1980’s.

On the river trip, she stopped to visit a coal mine – “well run and the men seem cheery”. She experienced the worst storm of thunder, lightning, and rain she had ever seen – “the Yangtze rose 12 feet in the night, and no-one spoke or moved during the storm.”

After repairs to the boat, damaged by the storm, she reached Chungking, “the westernmost of the treaty ports”, on 1st June.

After a few days rest at the British Consulate, she embarked on a ‘steamer’ to return to Shanghai..

Postscript

Isabella Bird’s journeys were all remarkable. She was a determined traveller and, despite poor health, seemed to relish hardship and danger. Her photographs in China too are outstanding and record scenes, people, and structures of historical importance.

More than this, her views, that she boldly expresses, intrigue, entertain, and sometimes annoy us.

She was ahead of her time but also of it.

She deplores that the British occupied cities of a civilisation far older and more sophisticated than theirs. Yet, she is reassured by the sight of a British gunboat on the Yangtze. She is critical of the attitudes of some of the foreigners she met yet relies on the help of British missionaries at every stage of her journey.

Some of her most forceful words are about the growing and widespread use of opium among so many Chinese people. Yet, at no point, does she refer to the British involvement in the opium trade. She is appalled by the rioting and anger that accompany her in almost every village. Yet she ignores (or possibly never knew) of the two Opium Wars started by the British when the Chinese Government banned the sale and use of opium. The second opium war ended when she was in her 20’s and resulted in major Chinese concessions to the British in territory, influence and trade.

The animosity this caused among Chinese people cannot surely have been a surprise to her – but it appears to have been.

Western governments, keen to ‘restrain China today, would do well to reflect on their own lack of restraint less than 150 years ago.In conclusion, Isabella’s words:

China…finds herself confronted by an array of powerful, grasping and not always over-scrupulous powers., bent…on over-reaching her and each other, ringing with barbarian hands the knell of customs and polity which are the legacy of Confucius. They clamour for ports and concessions and bewilder her with reforms, suggestions and demands of which she sees neither the expediency nor the necessity.

How little has changed!

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang