Kingdom of Characters

I have just finished one of the most fascinating books I have enjoyed in the last few years. “Kingdom of Characters” is ‘ tale of language, obsession, and genius in modern China.’ It is also a charming history of unusual aspects of the turbulent 100 years in China following the decline of the last (Qing) dynasty. Its author, Jing Tsu, is Professor of East Asian languages and Comparative Literature at Yale University. She emigrated from Taiwan to the USA aged nine. There is so much colour and life in this book. This review of a few pages cannot do it justice. I urge you to read it!

Background

A century ago, China was a crumbling empire with literacy reserved for the elite few. As the West underwent massive technological transformation, it left China behind.

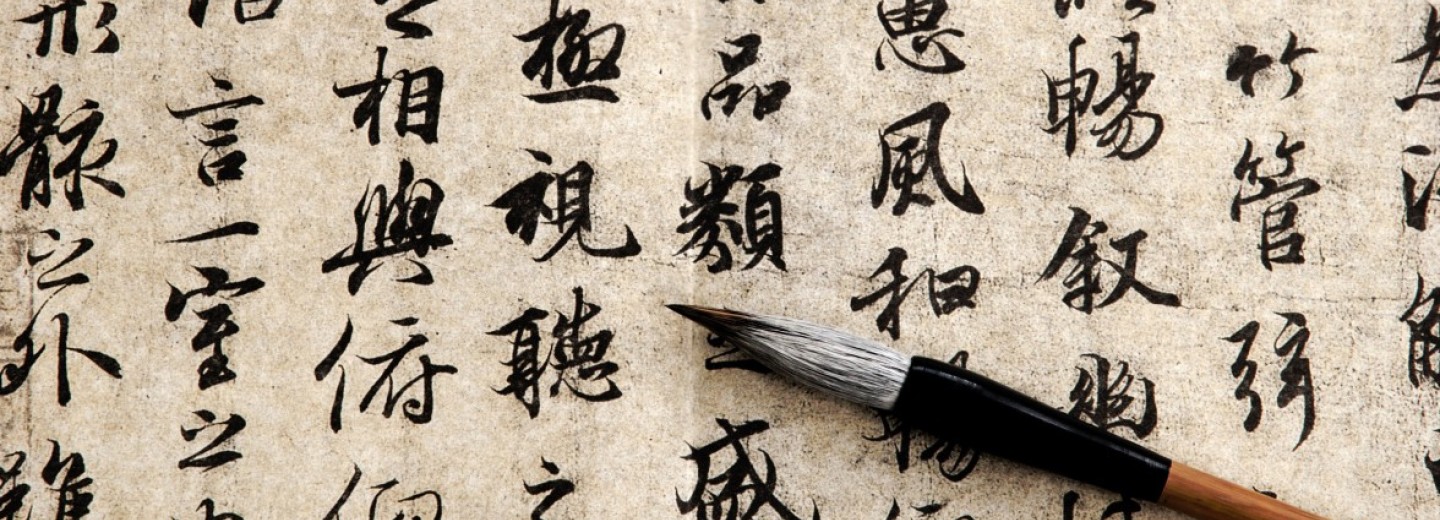

Chinese is the oldest living language and is spoken by the most people. Chinese is currently used by more than 1.3 billion people, not counting those who learn it as a second language. In 1900, Its written form had remained largely unchanged since it was first standardised more than 2,200 years ago. How an entire civilisation evolved to have a writing system as complex and massive as the Chinese script is an enduring linguistic mystery.

In contrast, linguists see the 26-letter western alphabet as a system that forms the bedrock of western science and technology. It is largely responsible for the West’s accomplishments.

Yet this complex construction of brush strokes and tones has been a crucial building block of Chinese culture. It was – and is – difficult for the Chinese to consider abandoning it. From the start of the Opium Wars in 1839, dedicated intellectuals, teachers, librarians, inventors, and language reformers embarked on some of the most extraordinary revolutions of recent times.

This is the subject of Jing Tsu’s book.

Early efforts

We read first of Wang Zhao, who returned to China in 1900 from exile in Japan, disguised as a monk. He was under threat of arrest on charges of treason brought by Dowager Cixi, the de facto Empress. Wang’s desire to go home eclipsed his fear of capture. In his robe, he kept a thread-bound pamphlet. With this, he intended to help China’s masses of poor peasantry escape their fate by building a bridge of education and understanding using the Chinese language. With just 62 elemental parts of Chinese characters scribbled by hand, he created a phonetic notation system for indicating how whole characters could be read aloud.

Chinese characters were usually learned by sight rather than by sound. Wang was part of a small group of forward-looking language reformers who wanted to speed up the learning process.

In our country, you cannot find a single person out of 100 who knows it. As a result, they are incapable of acquiring knowledge or of grasping politics, geography, or the appropriate relations between those who govern and those who are governed.

Wang was eventually rehabilitated and promulgated his ideas with some success and fame. He blazed a trail for phoneticizing Chinese that others took up.

Mechanical writing

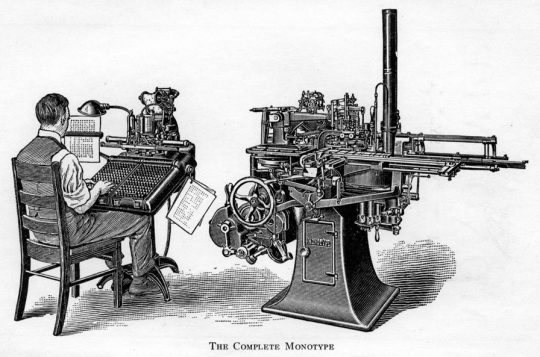

Jing Tsu’s next hero is Zhou Houkun, an engineer who left China to live in America. In 1912, while wandering around an engineering exhibition, he spotted a magic machine spewing out a reel of paper with holes cut out. It was a Monotype machine. The typist used a keyboard to punch holes along a reel of paper. This then went into a machine which produced clear, fresh, type.

Zhou realised that China still relied on antique typesetting technology to print its complex characters. This huge amount of time and effort was the greatest obstacle to the country modernising. He was eager to tackle this problem.

While Wang Zhao had tackled spoken Chinese dialects to establish one common language, Zhou Houkun believed that the answer to reform lay in modern technology, rather than philosophy or brush strokes.

The technical difficulties for manufacturing a Chinese typewriter were immense. A usable keyboard for a Chinese typewriter seemed unachievable. The Western keyboard worked because it easily manipulated a small number of letters in endless permutations. Chinese characters numbered in the thousands. These required a mechanical way to deliver one character at a time, but also able to be shifted to produce the other thousands of characters. How could a typewriting machine, originally designed to manipulate 26 letters, mutate into one that could produce several thousand characters?

Zhou realised that the average reader’s vocabulary used only 4,000 core Chinese characters; this was the machine he wanted to build. In 1915, he unveiled his machine to fellow Chinese students at MIT. Awestruck by the 40-pound machine, they invited Zhou to introduce his invention in the Chinese Students magazine. In the summer of 1916, Zhou returned to Shanghai. After several successful public demonstrations, he visited the main office of the Commercial Press in Shanghai. Its CEO then was a distinguished imperial scholar. He was keen to have Zhou on board.

But after ten months, only a perfect prototype had materialised. The CEO looked for someone hungrier and more eager to takeover Zhou’s project.

Shu Zhendong was a graduate from Shanghai’s Tongji university. He improved on Zhou’s prototype by eliminating some of the complex mechanical parts altogether. On the third try, he brought out a version that was fit for marketing. The Commercial Press put everything behind the final product.

At the Philadelphia international exhibition in 1926, Shu’s typewriter won the Commercial Press medal of honour for its ingenuity and adaptability.

The problems of telegraphy

Meanwhile the West was moving ahead with telegraphy. The first successful telegraph cable was laid under the Atlantic Ocean in 1866. Telegraphy was seen as the harbinger of peace and prosperity. However, Morse code recognised only the Roman alphabet and Arabic numerals used by most of its members. This meant that the Chinese too had to use letters and numbers. China suffered for being a latecomer to international telegraphy and its disadvantages grew with time. The only viable route for making telegraphy more equitable for the Chinese language was diplomacy.

Although many tried, curiously, it was a Frenchman, Septime August Viguier, who came up with the first solution to bridge the gap between Morse code and the Chinese language. The first Chinese telegraphic code was born because of his efforts. Subsequently, modified by Chinese contributors, in 1929, the new code was adopted.

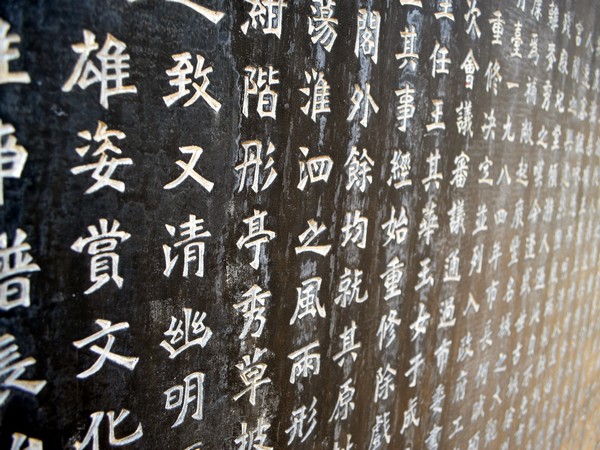

The answers to the problems of typewriting and telegraphy were important evolutionary steps to fit Chinese characters into technologies designed for alphabetic languages. Jing Tsu explains in detail the complexity of writing Chinese characters and their composition. The Western alphabet is simple. Many wondered if the real problem was the Chinese script itself.

Modifying the script

In 1917 Lin Yutang, a young teacher of English, started to design a different way to write Chinese characters. If one could find the character easily in a dictionary, one could just as quickly locate the first character of the title of a book. Lin’s index method drew attention to what China needed to do to preserve its cultural legacy. He started the journey to complete what became known as the character index method to organise the Chinese script.

Many new ideas and dictionaries followed in the 20’s and 30’s. Then political events and wars slowed many of the developments. Jing Tsu tells the story of librarian, Du Dingyou, who was ordered to evacuate the city of Guangzhou as the Pacific war had advanced to a new stage. When the bombs started to fall, his pressing thought was for all the precious, dusty books on the shelves in storage. They were still under his stewardship. He packed up about 300,000 volumes. And took them to the crowded dock, joining a mass of refugees hauling their earthly belongings.

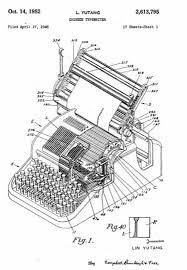

After the end of hostilities in 1947, Lin Yutang realised he had finally built a viable typewriting machine. It was to set a precedent for a not-so-distant future of computing shared by both China and the West. Lin had spent decades developing the Chinese keyboard to you to be used in the simplest most straight forward way.

He filed a patent in the USA in April 1946 and went to see the Remington typewriter company. Lin gave a general introduction and explained how his machine was the solution to easily reproducing mechanically the Chinese script. However, as his daughter sat down to demonstrate the working of his machine, the typewriter malfunctioned! The malfunction was easily fixed but he had lost his chance with Remington. Inventing the machine was easy but commercialising it was hard.

However, others were quick to take up the offer and Mergenthaler offered him a contract to develop the machine.

In the years between the time Lin filed his patent application and its approval in 1952China underwent its last big political transformation of the 20th century.

A strong hand now guided China’s linguistic path.

The Peoples Republic of China

In the 1930’s, the Communists had taken up the cause of simplification. Under Mao Tse Tung’s leadership, important legacies would leave an indelible mark on the modern face of the Chinese script. Ironically, Mao spoke and understood only the Hunan dialect where he was born. But he caused the development and introduction not only of a more simplified Chinese script but also its Romanisation – originally begun by Christian missionaries in the 15th century. In 1954, the committee on script reform published its first draft of an official simplification scheme. A list of 798 characters was formally introduced the following January to great enthusiasm. 97% of 200,000 individuals polled around the country approved of the simplification of scheme. The simplified script was the cultural legacy of new China’s triumph over the Nationalists.

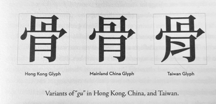

With the dawning and the rapid development of the computer age, the work done over the previous century needed further improvement. The Ideographic Research Group has been meeting twice a year for more than 25 years. The Han script is the only writing system that has its own international working group. The IRG discusses the nature of Chinese characters in the computer age. It meets regularly to reconcile the differences between the various scripts, for example in Hong Kong, the PRC, and Taiwan. In her book, Jing Tsu shows how variants of character need monitoring in the computer age.

Conclusion

This book is exceptional in its breadth, humanity, and historical interest. Jing Tsu’s greatest gift is to explain the complexities of Chinese to us. She also slips in delightful details of the characters and events that helped shape modern Chinese. The last words below to Jing Tsu.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang