Re-writing history

I am reading John Keay’s ‘History of China’. Mr Keay makes the point that historians base their accounts of past events on contemporary sources. For example, much of what we know about early Chinese history comes from four texts, all written around 100 years after the events they describe. But how reliable are the histories on which we base our opinions?

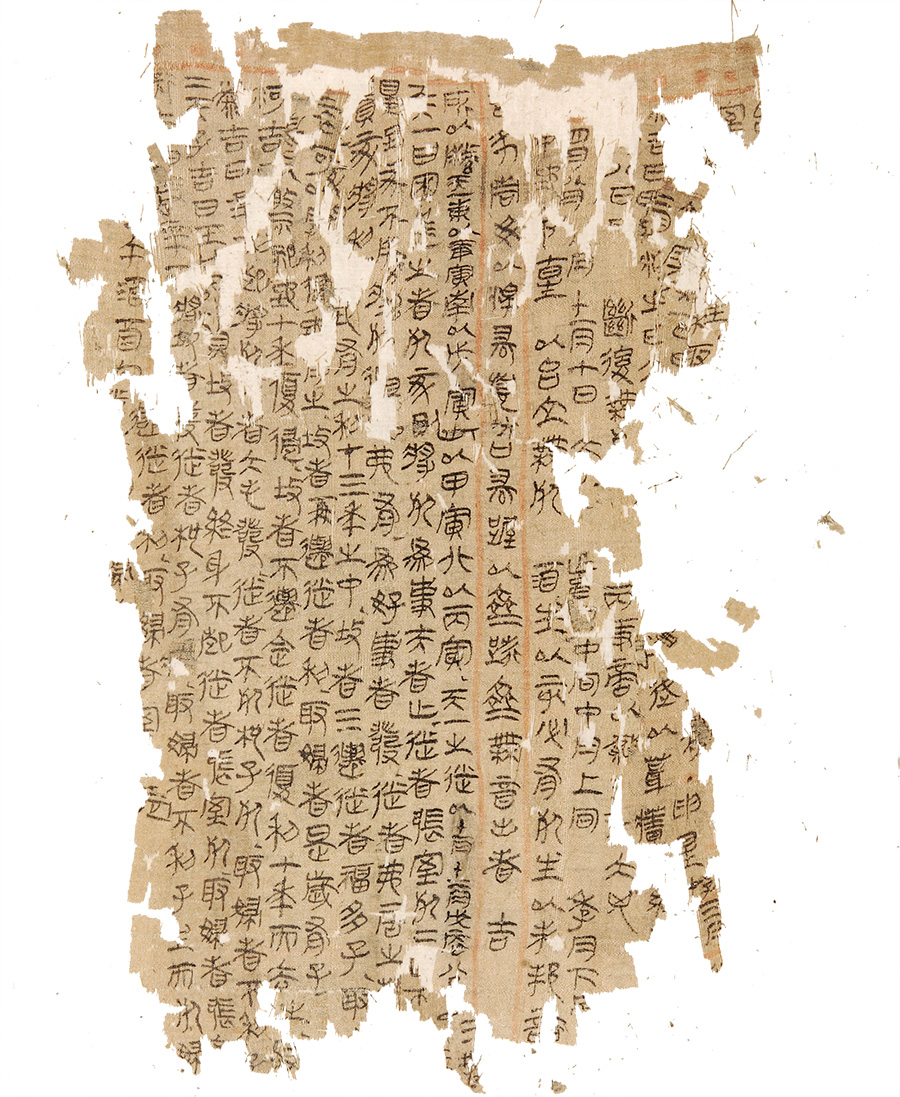

China

That the Chinese texts exist at all, and are legible to scholars today, is remarkable. Their words, supplemented by other (often commercial) evidence written on bamboo sticks has provided historians with rich research from which to make conclusions.

For 2,000 years before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, most educated people believed Emperor Qin, ‘the first emperor’, to be a cruel and wicked man who justly died only a few years after uniting China. His name was a synonym for evil. No serious historian compared him favourably to other dynasties, however chaotic they may have been. “Only when patriotic nationalists revived the memory of Qin’s first ever unification of China, and when Marxists and Maoists discovered the revolutionary credentials of its despotic instigator would Qin cease to be a dirty word,” writes John Keay.

England

In the same way, most people believe that King Richard III, the last Plantagenet king of England, was an evil hunchback. Richard murdered his way to power by killing two young boys who may have had better claim to the throne than he did. Shakespeare’s play, Richard III, probably accounts for most of Richard’s bad reputation. The play is clever, dramatic, fiction. Thousands of theatre and movie goers around the world have watched famous performers take leading roles. Shakespeare wrote his play 100 years after Richard’s death in battle at the hands of the Tudors, the dynasty that replaced the Plantagenets. Richard was the last English king to be killed in battle. It must have been politically very convenient for Shakespeare to celebrate the Tudors’ justification of their rule by destroying the ‘wicked tyrant’, Richard.

In September 2012, researchers found the remains of Richard III under a car park at the site of a former Priory in Leicester. Following extensive testing, archaeologists agreed to bury the body at Leicester Cathedral in March 2015. The group organising the search challenges the popular view of King Richard III by demonstrating that the facts of Richard’s life and reign are in stark contrast to the Shakespearian caricature. English author, Josephine Tey’s last novel, Daughter of Time, is one of the best-known fictional defences of Richard’s life and reign.

Which is correct? Was Richard III a tyrant or a successful monarch?

Neolithic China

In another reference to more nuanced views of Chinese history, John Keay quotes the provincial museum in Hangzhou that contains a display of the relics of the Hemudu culture flourishing in the area in at least 5,000 BCE. ‘The excavations…have proved that the Yangzi River Valley was also the birthplace of the Chinese nation as well as the Yellow River Valley’.” (For hundreds of years, this was the accepted version of the start of Chinese civilisation.) “Until recently,” writes Mr Keay, “this would have been heresy. A Chinese scholar in the early 1980’s tentatively questioned the accepted view as incomplete; one might now call it downright mistaken. Many archaeological sites exist proving that China contained dozens of neolithic cultures, none of which was more advanced than the others.”

Why does this happen?

Why do historians get it wrong? Is it merely political correctness? Like us all, historians are products of their time. It takes courage to put your reputation (and in some cases your life) at risk by challenging accepted thought. But there is more to it than that.

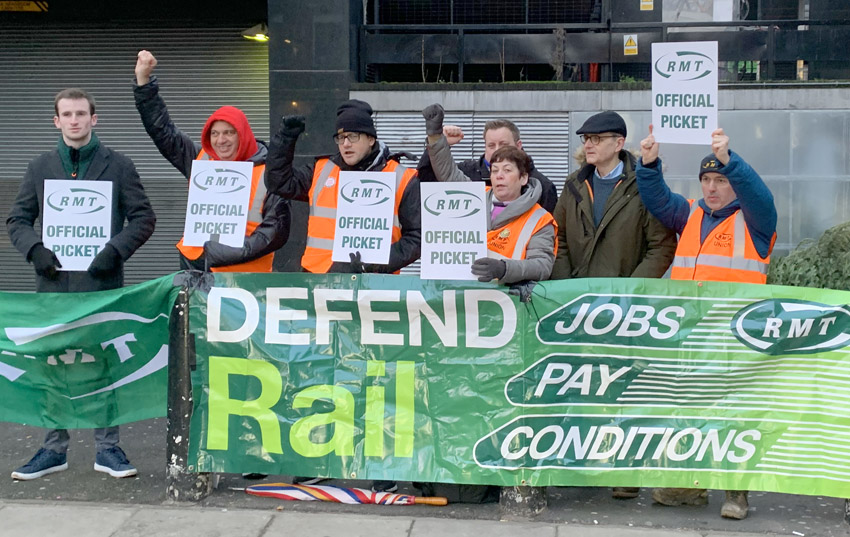

The UK at present is beset by striking workers in the public services. Train drivers, bus drivers, nurses, ambulance drivers, all demand more pay. The people they serve, the British public, have mixed views. Supporters of left-wing politics enthuse about the strikes and urge more workers to join the ‘revolution’. “Workers should step up strikes to derail Tory strategy”, exhorts the Socialist Worker with glee. The advocate of revolution, News Line goes further:

TORIES WANT MASSIVE CUTS – GENERAL STRIKE NOW!

Yet, the right-wing Daily Telegraph says:

Commuters will suffer the worst single day of strike action during a working week for decades as just one in 10 train services runs on what is being dubbed ‘Tragic Thursday’.

It forecasts further declines in rail travel to the cost of rail workers’ jobs.

If one were, say, a trade union historian, one might write a somewhat different version of the history of this period, from that of a businessman or a right-wing political historian. Readers of history would believe the version of events that fitted their own views.

In this blog, I sometimes contrast the western media’s view of the Hong Kong rioters as ‘brave young people fighting for their rights’ with the treatment of protestors elsewhere. In the UK, environmentalists who cause ‘major disruptions to the long-suffering public’ by damaging paintings and gluing themselves to railings, trains and motorways are ‘breaking the law’. The police have prosecuted them, as Hong Kong prosecuted its rioters. Both groups of protestors complained about ‘police brutality’. But why the different media treatment?

When it comes to national history and current events, each generation and each culture learn different lessons from the media and their history books. We believe what we want to believe.

But there is more to it than that.

Science

A recent article in one of my favourite newsletters, Aeon, discusses fascinating recent research into man’s impact on the environment:

While some aspects of…early global climate change remain unsettled among scientists, there’s strong consensus that land-use change was the greatest driver of global climate change until the 1950s, and remains a major driver of climate change today…By 3,000 years ago, Earth’s terrestrial ecology was already largely transformed by hunter gatherers, farmers and pastoralists – with more than half of regions assessed engaged in significant levels of agriculture or pastoralism…In the ‘pristine myth’ paradigm from the natural sciences, human societies are recent destroyers, or at the very least disturbers, of a mostly pristine natural world…(but) Humans have continually altered biodiversity on many scales.

I make two points here: firstly, these conclusions are due to greatly improved science. Archaeology, and its offshoots, enables experts today to understand more about what happened thousands of years ago than ever before. Just as archaeology in China shows us how mistaken historians have been about Chinese history, so too, scientists now throw new light even on a topic as broad as global warming.

Environmental studies will change as a result. We will learn more about our world. We will realise that previous ‘facts’ about a ‘pristine world’ were wrong. And, in turn, the conclusions the Anthropocene Working Group has reached today will doubtless change tomorrow as new science emerges.

Secondly, please read the whole article if you have time. I have quoted some sentences to show the essence of quite a long article. But if I were a climate change denier, these are the sentences I might choose to support my views. ‘All this climate change talk is rubbish. We’ve been doing it for years. Why disrupt our lives so much today?’

For balance, here is the report’s final paragraph:

We live at a unique time in history, in which our awareness of our role in changing the planet is increasing at the precise moment when we’re causing it to change at an alarming rate. It’s ironic that technological advances are simultaneously accelerating both global environmental change and our ability to understand humans’ role in shaping life on Earth. Ultimately, though, a deeper appreciation of how the Earth’s environments are connected to human cultural values helps us make better decisions – and also places the responsibility for the planet’s future squarely on our shoulders.

Conclusions

As with all writing, some of what we call ‘history’ is politicised. Not only that but historians, being human, make mistakes and sometimes come to wrong conclusions. But the biggest contributor to understanding better what happened in the past is science. Every time someone explores a new archaeological site in China, history is likely to change. Even looking at previously accepted research with new techniques, may deliver different outcomes in many branches of history.

It is not just the present that constantly changes. So must our perception of the past.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang