Tales of the Silk Roads

“The Silk Road – a New History”

In this post, we look at some of the artifacts and personal stories of the Silk Roads that archaeologists have uncovered in the last 20 years. Professor of History at Yale, Valerie Hansen’s book “The Silk Road – a New History” provides many charming insights into some of these. We have picked just a few to illustrate the phenomenon of the Silk Roads.

Professor Hansen opens her book with a photo of some recycled paper on which are Chinese characters. They record testimony given by an Iranian merchant living in China around 670 CE. The Iranian wanted the court’s help to recover 275 bolts of silk owed to his deceased brother by the brother’s Chinese partner. The court ruled in his favour.

The Silk Road was one of the least travelled routes in human history and possibly not worth studying – if tonnage carried, traffic, or the number of travellers at any time were the sole measures of a given route’s significance. Yet the Silk Road changed history, largely because the people who managed to travel (it)…planted their cultures like seeds of exotic spices carried to distant lands.

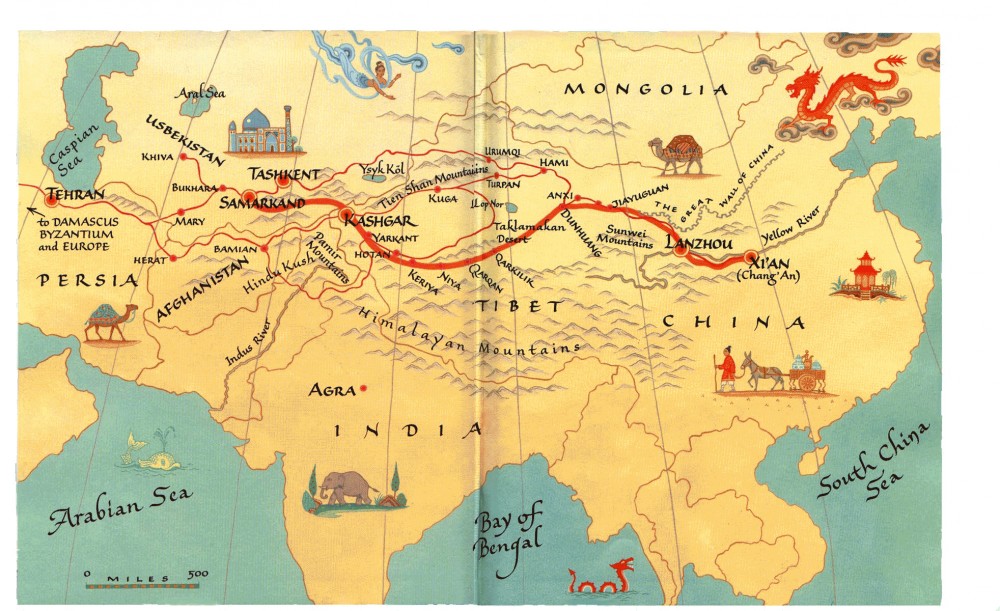

The routes of the Silk Road date back to human origins. In prehistoric times, whole populations migrated along them. Later, the most influential people moving along the Silk Roads were refugees brining their languages, skills, and trades. The most prominent of these were the Sogdians who came from what we now know as Uzbekistan.

Evidence

The earliest evidence of trade comes from a piece of jade that travelled from Khotan in western Xinjiang to Anyang over 4000 kilometres to the east, in about 1200 BCE. The Hejia Village Hoard of over 100 beautiful gold and silver vessels were made around 730 CE. They were discovered in modern day Xian and were produced by Sogdian immigrants using jewels imported along the Silk Road.

Professor Hansen points out that merchants along the Silk Road prospered ‘because of the massive presence of Chinese troops” that kept the road safe. However, after 755 CE and rebellions against the Tang dynasty, the economy of the Silk Roads collapsed for many years because the China could no longer keep merchants and travellers safe.

In a foretaste of BRI, Hansen describes the major transfer of wealth from China to the west in 730-740 CE. 900,000 bolts of silk helped subsidise the economies of what is now Gansu and Xinjiang.

The reason all this is known today is also dramatic. In 1900, a monk discovered a sealed entrance in the Mogao Caves in North West China, where tens of thousands of manuscripts, paintings and other artefacts had been deposited and sealed up around the beginning of the 11th century. The world’s oldest printed book, the Diamond Sutra was found in this Buddhist centre. Printed in 868 CE, it was brought to England by the explorer Sir Aurel Stein in 1907.

Thousands of wooden slips discovered in the caves document the regular exchange of envoys between China and rulers to the west. Not only that but they are written in many different languages. One of the most interesting documents, on a sheet of early folded paper, records sections of the Psalms in Hebrew. Then there are the Manichaean hymns that would have been sung in Sogdian but were written phonetically in Chinese characters!

The people of Khotan had to become adept at learning many different languages as theirs was the centre through which many travellers passed. Among the many texts discovered are language textbooks. They include simple phrases in several languages:

“How are you?”

“Good thank you!”

“And how are you?”

“Where do you come from?”

“I come from Khotan.”

“Bring me vegetables!”

Among the many thousands of ‘documents’ there are contracts, legal cases, receipts, cargo manifests, medical prescriptions. There are details of a slave girl sold for 120 silver coins over one thousand years ago. Wonton and Dim Sum dumplings from the 6th century were found, preserved in the dry air of the desert. The desert also preserved some tombs of people with western physique and clothing.

All this was unknown to Europeans until 1895. Since then, several notable travellers have studied the Roads’ many communities and uncovered countless treasures. Many of the latter are now in western museums. By modern ethics, this was plunder. All one can say is that at least they still exist. Archaeology is happily continuing to find new places of interest and new insights.

Professor Hansen concludes that the dry desert conditions enabled explorers to discover multiple documents and artifacts from long ago.

Those same conditions draw visitors today who hope to catch a glimpse of the latest discoveries from this now lost, once tolerant, world.

Tolerance of some kind there may have been. But the Silk Roads were also lonely and dangerous. Apart from frequent wars, raids and invasions, travellers faced bandits and minor criminals at almost every stage. Sometimes there were small armies of raiders. Always there was the cold of the mountains or the blazing heat of waterless deserts.

Yet the urge to travel, to trade, to exchange ideas and explore beliefs has existed for as long as humans have walked. 1.5 billion tourists explored the world in 2019. Few experienced the hardships of the early travellers on the Silk Roads.

But now, as then, the world and those who have travelled are enriched.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang