The Silk Roads. Part 1

On my desk is one of the most beautiful books I have owned in a lifetime of enjoying books. “Silk Roads” is edited by Susan Whitfield and published by Thames & Hudson.There are many books about the so-called ‘Silk Road’. This is the loveliest, most scholarly and beautifully produced. It looks like a coffee table book with its wonderful photographs and illustrations.

It is far more than that.

The book’s deeply researched contents draw on no less than 600 books and papers. 82 academics and historians contributed their work and advice. If there were only one source of deep knowledge about a fascinating part of human history, this would be it.

I will draw upon this book for this and future posts about the Silk Roads.

China’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiatives are an important part of the story today. Peter Frankopan’s 2018 study, “The New Silk Roads”, describes the background to and purpose of ‘Belt and Road’. More recently, Chatham House, the 100-year-old London based research institute, produced an excellent study on ‘Belt and Road’. I will use these and other materials to discuss the modern Silk Roads.

In this first post about the Silk Roads, I will begin at the beginning – to the extent that there is one.

Background

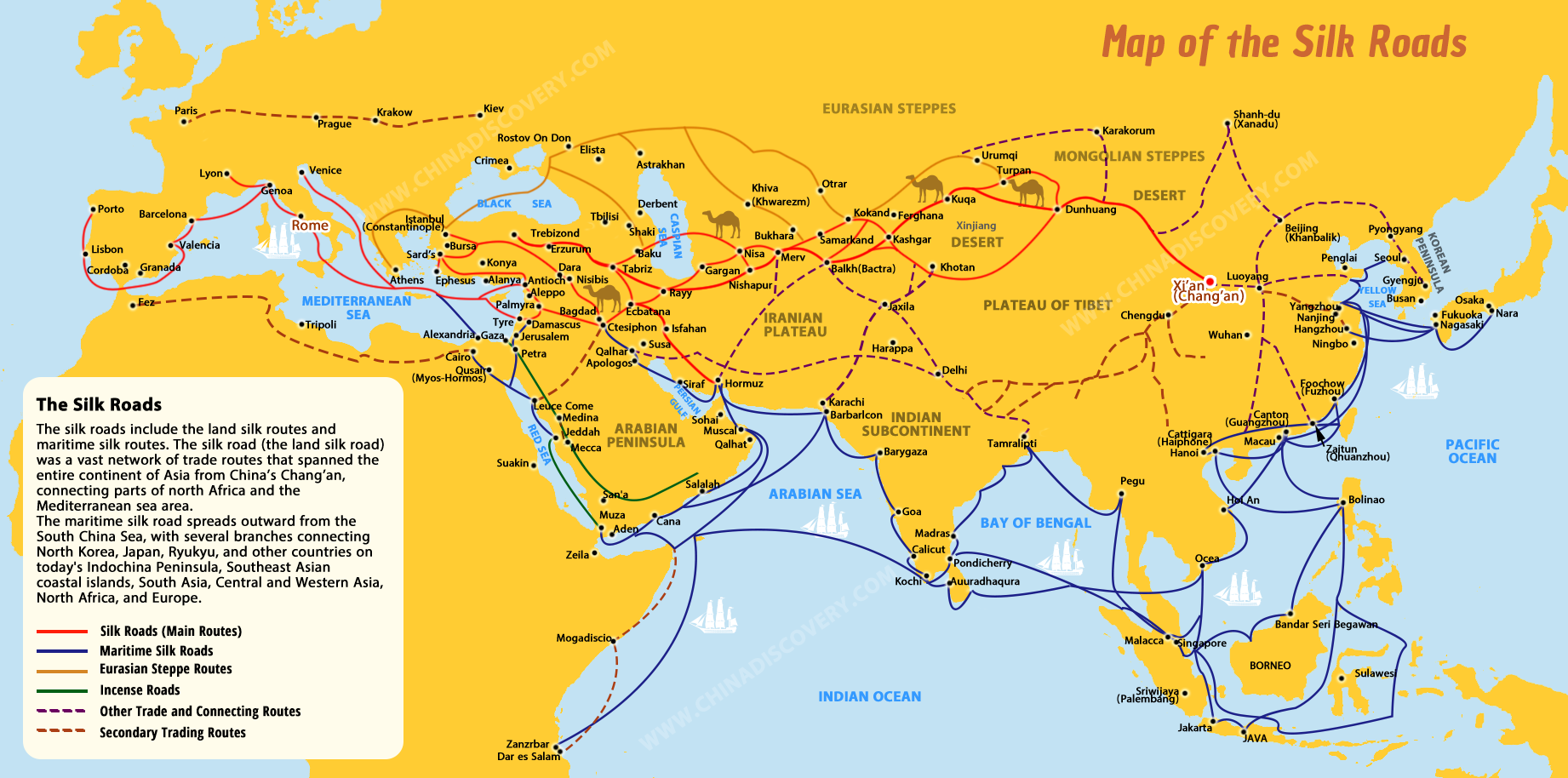

There is no ‘Silk Road’ – and there never was. It is a 20th century term to describe a complex pattern of trading across Asia, Africa and Europe. This exchange began sometime in the middle of the second millennium BCE. Horses, metals, technologies, religions, music, stories and much else travelled in both directions. And not only by road. Many sea routes ferried people, animals, plants and goods between ports in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. People and animals travelling by both land and sea also brought medicines and diseases.

Study of the Silk Roads, even with help from excellent books, is daunting. Many of the routes cross remote areas of the planet. Because of this they have escaped the attention of scholars. Anthropologists and archaeologists are frustrated by climate, wars and pilfering. The size and scale of the trade generated was astonishing. The many routes used are complex and confusing. The map below shows just a few of them.

Arguably the Silk Roads’ most famous traveller, Marco Polo, left Venice one day in 1271 to return 24 year’s later from ‘Cathay’. He was then imprisoned for debt and dictated his story to a fellow prisoner. It became one of the most popular books of that age. Today Polo’s visit to China is taken as a matter of historical record. He appears in the names of everything from travel agencies to a model of camper van, to a class of air travel. Though bemoaning the lack of maps, even “Silk Roads” takes his journey for granted.

Yet in her book “Did Marco Polo Go To China”, published in 1995, Frances Wood argues that he never went to China and probably never ventured past his family home on the Black Sea. Instead, his imagination, fuelled by stories from other people and with the help of his felonious ghost writer enabled him to publish his renowned ‘adventures’.

Then again, in 2012, further research by Hans Ulrich Vogel of Germany’s Tubingen University, tries to restore Marco Polo’s integrity. In a book entitled “Marco Polo Was in China,” the professor of Chinese history counters the arguments most frequently made by sceptics. He ‘proves’ once and for all that the Venetian wrote the truth.

It does not matter much to most of us if Marco Polo really went to China or not. It is a fine story. The scholarly arguments will continue in any case. But the debate illustrates how difficult it is to be sure about many aspects of the Silk Roads. Over 2000 years, so little evidence survives.

As an example, editor Susan Whitfield writes: ‘The economics of the Silk Roads remains a large gap in our knowledge.’ And: ‘the same can be said for the major religions of the Silk Roads. (For example) early Christianity is often associated with desert sites, but Christians also sought out mountain retreats…once the religion grew more institutionalised it became powerful in the cities on the rivers and plains…and was transported by sea to distant ports.’

Music and dance too, travelled the Silk Roads. Manuscripts in various languages still survive. They represent just a tiny part of the richness of spoken languages across the many regions through which the Silk Roads (and voyages) passed. The Silk Roads have played a major part in the history and culture of Asia, Europe and Africa for over 2000 years.

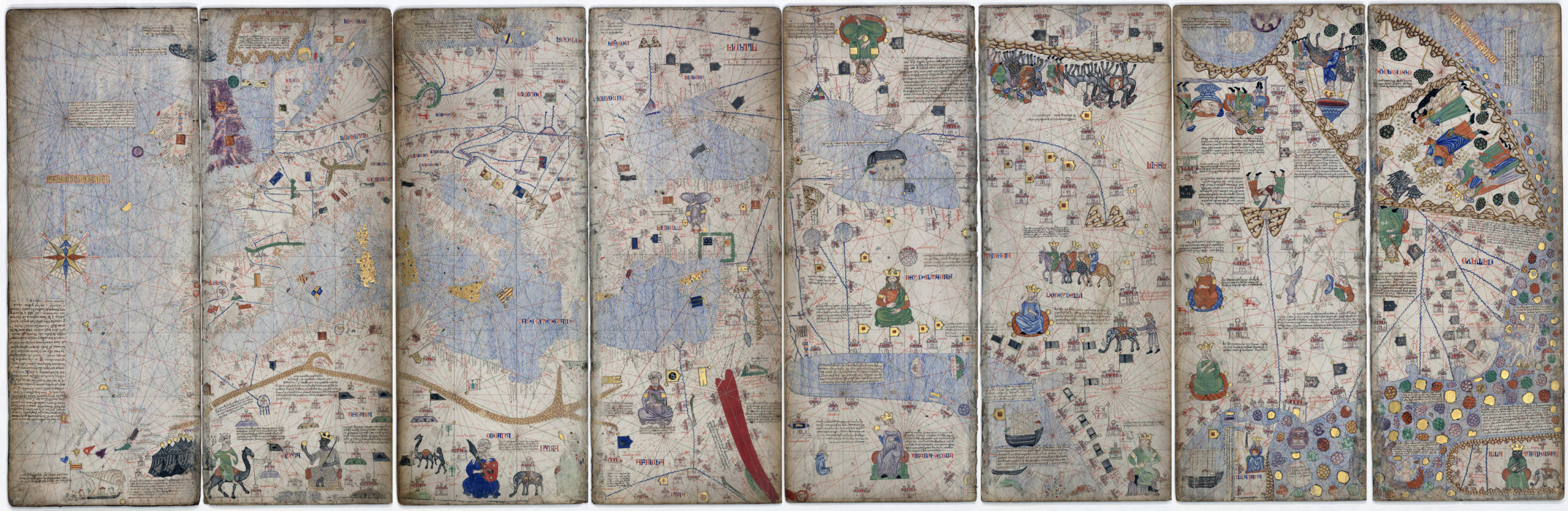

Drawn in around 1375, the famous Catalan atlas shows how important they were to Europeans then. The map contains rich spectrum of written and pictorial stories, many of them imagined.

Today, as then, our knowledge is incomplete. ‘Known facts’ may not be facts. Yet the impact on the lives of all Europeans, Asians and many Africans made by the travellers of the Silk Roads is as evident today as it was when Marco Polo wrote his book. History, as it always does, is repeating itself.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang