Why have outdated education?

In this post we look at the appalling state of education in every country. What is education for? Is the industry delivering on the objectives? We believe categorically not. In every country, billions of dollars are wasted on futile learning. This has to change. But how?

Consider these quotes:

The (education) system (in my country) focuses way too much on scoring points and only learning what will reward you superficially on a short-term basis, the whole thing feels very cynical and narrow-minded. I find it funny that on one hand, parents and teachers are obsessing about making children into the perfect worker drones but on the other hand they complain that kids these days have no creativity.

For (this country), lasting and positive changes to education cannot and should not be mandated by the government. Instead, forward-thinking schools should take note of the effective approaches found abroad, and they should consider how they can extend educational freedom to their own constituents.

When the tests were last undertaken in 2012, Shanghai – which represents China in the tests – was ranked first in maths, reading and science. (This country’s) respective rankings were 26, 23 and 21. Besides falling behind Hong Kong and Japan, (this country) was beaten by Finland, Ireland and Poland.

The forward momentum of (this country’s) education cannot be resisted: a relentless fascist machine that will spit them out the other side as soldiers or sexless governors-general and the like. All (a teacher) can do is plant some small seed of independent thought in their minds. He is sorry for them and what is coming: every rottenness and corruption.

These are some of thousands of comments one can find in the public domain (that’s Google to you and me) about every education system in the world. Three of the quotes refer to education in two countries that many regard, in Asia at least, as world leaders. They are the aspiration of many parents for their children – the USA and the UK. I leave you to guess which is which, and which place the fourth comment (I do not mean the last) is from.

It seems that every country wants to emulate what they see of value in other countries’ education systems. The Chinese education system and Hong Kong and Singapore is admired in the USA and UK for its exam results and the discipline it generates. But Chinese parents want their children to learn overseas. They believe the systems in the UK and USA are more creative and will help students get better jobs.

Self-analysis and self-improvement are good for us all. Thus, ‘experiments’ abound where teachers from one country try to teach in another. Almost all fail. Earnest groups of educational experts scour the globe seeking the truth about why this country does so well – and why their country does not. Yet they can rarely transfer these lessons to their own countries.

Finally, the examination system, which educationalists see as critical (‘how else can we measure our results’?) causes increasing unnecessary stress to young people – pointlessly.

Cost

And education is not cheap. The World Bank estimates that 14.1% on average of national expenditure globally is spent on education. In Hong Kong it is 17.8%. The UK spends a ‘mere’ 13.9% and the USA 13.5%. The last figure for China was 9.43% in 2016. The teaching industry is huge.

Yet, almost everywhere, parents criticise the education their children receive. The older generation pays a lot to raise a younger generation about which they then complain!

So – why do it?

We do not know for sure but human beings did not have any education as we define it today until perhaps, 10-15,000 years ago when we settled down to a post-nomadic life. You learnt as you went along. Some humans were brighter than others; some were more artistic; some worked harder. Knowledge-sharing was crucial.

The remaining life on the planet does not school its young. Tiger cubs play games and learn with the occasional cuff on the head from a parent’s paw. Many insects such as ants, bees and cockroaches achieve their goals through outstanding co-operation and common understanding. This has so far proved impossible for human beings.

So why do we put so much time, money and effort into education? Leonardo da Vinci, after all, received none.

The purpose of education

Although words differ over the centuries, there are generally accepted purposes for education. Confucius talked about raising the young to be ‘honourable’ and to ‘follow the way’. They could not go wrong in life if they did so. Mo Zi emphasised self-restraint, self-reflection and authenticity rather than obedience to ritual. Plato talked about preparation for life, doing good deeds, serving the community. Aristotle believed that education was central – the fulfilled person was an educated person. Throughout the ages, others have followed similar themes – prepare children for life.

I am fascinated by the work and thoughts of the American philosopher and educator, John Dewey (1859-1952). He spent two years in China between 1919 and 1921, helping develop the state education system. The very education system that is admired in parts of the world today – and yet often criticised in China – is centuries old. But Dewey believed he helped reinvigorate it. In 1934, long after his time in China, he wrote:

The purpose of education has always been to everyone, in essence, the same—to give the young the things they need in order to develop in an orderly, sequential way into members of society. This was the purpose of the education given to a little aboriginal in the Australian bush before the coming of the white man. It was the purpose of the education of youth in the golden age of Athens. It is the purpose of education today, whether this education goes on in a one-room school in the mountains of Tennessee or in the most advanced, progressive school in a radical community.

But to develop into a member of society in the Australian bush had nothing in common with developing into a member of society in ancient Greece, and still less with what is needed today. Any education is, in its forms and methods, an outgrowth of the needs of the society in which it exists.

(Notice that John Dewey mentions nothing about taking exams.)

Changing needs

This is the point – and one that many people miss. Education only has value in the society in which it exists. In a disciplined society, education is disciplined. In a more liberal society, it is less disciplined. Most Anglo-Saxon societies were more disciplined 100 years ago than they are today; so their education was likewise disciplined. Many others, Asia included, keep traditional disciplines; so their education is more disciplined now. We all have views about which suits us better; most will see there are advantages and disadvantages in both education styles.

More than this however, the things young people need to learn change – and they are changing rapidly now. In earlier epochs, men needed to learn how to fight, use swords and defend themselves and their families. Women needed to learn how to cook, raise children and nurse the sick. Today in some countries, both men and women do both and need to learn both.

Euclid and Pythagoras taught generations of western citizens the mathematical sciences. In China, mathematics and its teaching were developed by at least 200BC, (some believe earlier than that) though it fell into decline in the seventh century AD. The Greek philosophers taught logic and reasoning. It was also important to learn rhetoric, the art of public speaking as we would call it today. Chinese philosophers taught Confucianism.

And both Western and Chinese education owe much to the Arabs who kept alive knowledge of mathematics, medicine, art, music and science at a time when much of the western world was in grave disorder and always at war. Today the Muslim world still offers moral guidance to children – not normally available in most other education systems.

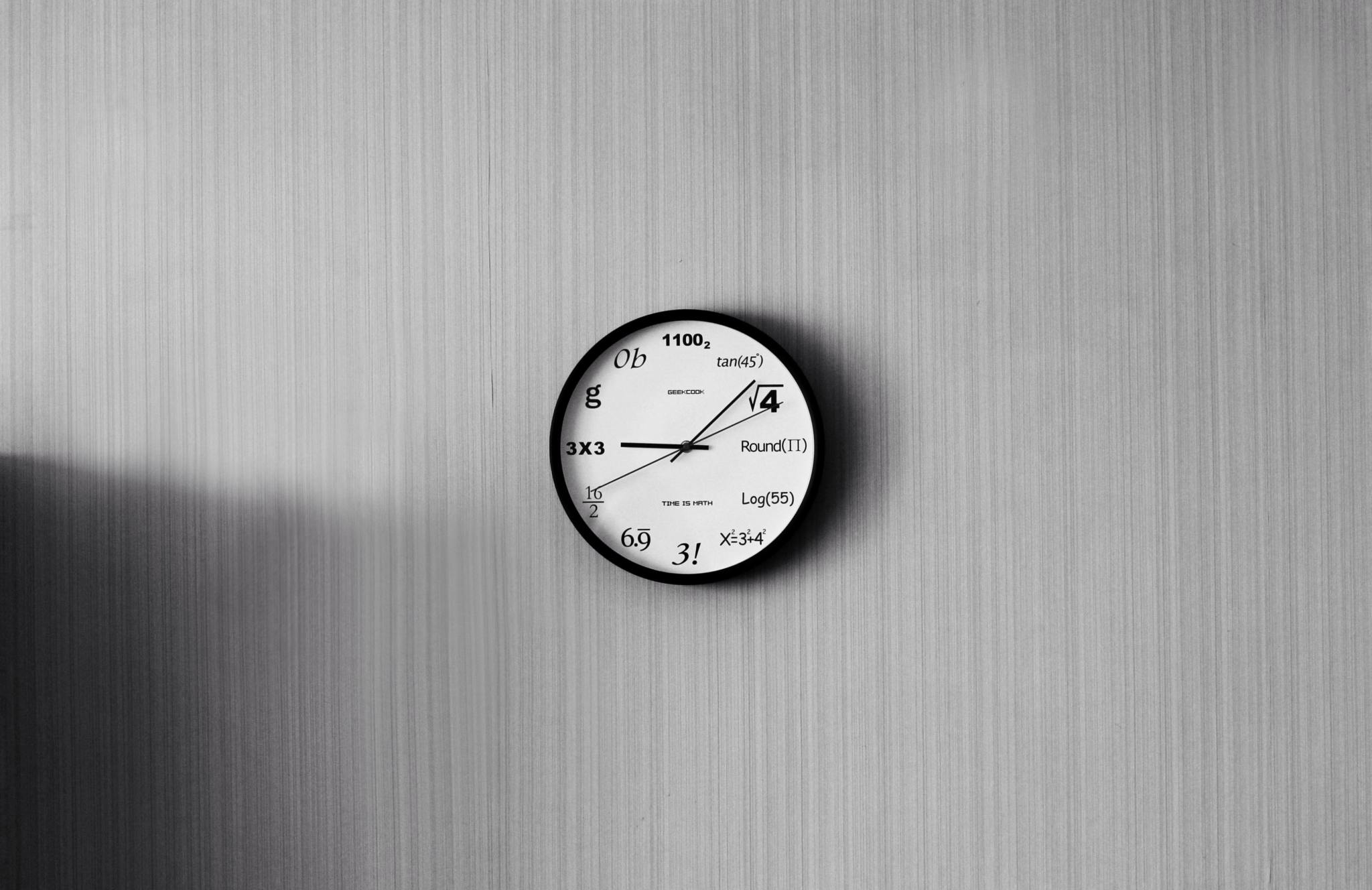

Yet today some argue that, for most people, mathematics teaching, for example, is irrelevant. A $10 app on a mobile phone is capable of calculations far more complex than any of us is likely to need. Even 40 years ago, I remember workers who could neither read nor write, knew to a penny exactly what would be in their pay packet each week from a complex and subtle, output based incentive scheme.

Again, why are we examining students so stressfully on subjects that are less and less relevant.

The problem

If we accept that culture plays a critical role in education and that successful education must fit the needs of the times, then, there is little doubt that:

- It is a waste of time and effort to try to emulate another country’s education system and, more important

- Most of what we teach today is not fit for purpose because it is founded on needs that are centuries out of date.

- Focussing on examination results produces great stress for little purpose in future life.

In 500 years’ time, education today will surely be looked on in much the same way as we now regard medieval sanitation (appalling), regardless of country.

So, what can we do?

Here is where it gets difficult because, quite literally, everyone has ideas, and most have a voice – that is around 7.5 billion opinions! Furthermore, the teaching industry employs over 70 million people according to some studies. It is impossible to visualise a global reformation of education. But two groups of citizens can play a part.

Parents

Over the centuries, parents have taken a major role in their children’s education. They have provided the context, values, and ‘life skills’; schools did the ‘academic stuff’. In many families this still happens. But more and more, contempt is growing between the teaching establishment and their clients. ‘Parents cannot be trusted to educate their children properly…’ educators say when talking about what should be in the curriculum, for example. ‘I think the school should do more (or should not interfere) in how I bring up my children…’ say parents.

Further education, graduate and beyond, reveals more issues. Jobs, careers, lifestyles, appear to depend increasingly on the magic initials or numbers depicting the qualifications of the aspiring employee. If these, as they do, depend increasingly on irrelevant or arcane knowledge, the time and resources spent acquiring high grades is a huge waste for both the individual and society. Yet parents insist on the best education possible for their children because that’s the way to the best jobs and careers.

But where do life skills rate?

Employers

Employers want the best people to work for their company. When a firm recruits young people with little or no experience of working life, how is it to choose between them? The obvious answer is education – the more advanced, the better a young person must be. Many top organizations, especially in Asia, think the same today.

This may be true for technical professions (medicine, the law, academia, accounting for example). But the vast majority of jobs, in both public and private sectors, need those who enjoy what they do and who share the organization’s values.

In many global companies, selection methods are changing to reflect this. Instead of looking first at the grades and content of a young person’s education, they look at their attitudes, social skills and ‘fit’ with the organization’s culture. Psychometric criteria (imperfect) and a battery of other assessment tools take the place of a strong c.v. and a short interview. In some companies a c.v. is almost irrelevant now.

Summary

Education systems are challenging and being challenged. In particular, what young people need to learn is changing very fast. Current curricula and methodologies no longer suffice. The outdated examination system plays a large role in student stress. Local cultures play a major part in education, yet global companies are demanding more personality-based rather than academic skills.

Bringing about change in education by any form of government intervention is impossible and undesirable. Those in the education industry are too close to it to bring about change.

Two groups can have a profound effect. Parents should be more involved with the non-academic aspects of their children’s schooling. Employers should continue to demand more relevance of education systems around the world.

And the young people themselves? They will find their own way as the young have always done. In doing so, in a time of profound change, they will make their own changes.

It would be a shame if we cannot help them do this better.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang