All Things Bright and Beautiful

Human beings need gods. Most of us believe in something bigger than us: something or someone to explain our joys and disasters. We give our gods human characteristics. They are happy with us, so they reward us. We misbehave by breaking their rules, so they punish us.

But who makes the rules? And how do we know what they are?

How some rules came about

In the 4th or 5th centuries BCE, the Buddha’s words were repeated orally. Several centuries later, the Tripitaka appeared in Sri Lanka, containing the Buddha’s teaching in writing. Buddhist values have become a significant influence in many parts of Asia.

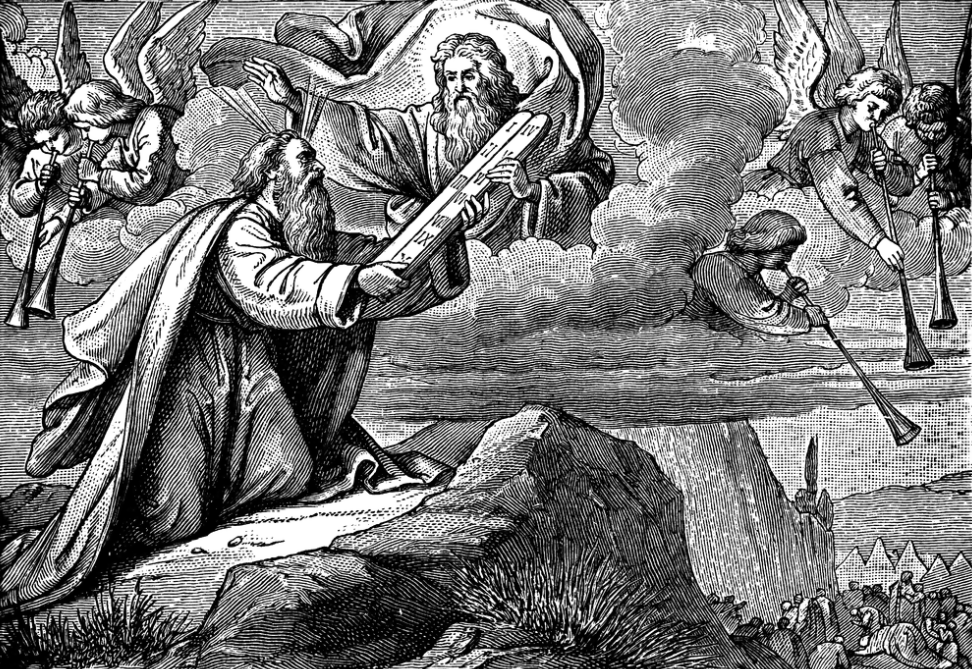

According to biblical accounts, God gave Moses the Ten Commandments. The Ten Commandments remain a robust moral code to this day. (Although, as I wrote in an earlier article, many of the sins they refer to are no longer taken seriously.)

The Jewish Tanakh forms the basis for much of the Christians’ Old Testament. A collection of laws and wisdom from different Jewish authors at different times, they are considered divinely inspired.

Later, in Jerusalem, the disciples of Jesus referred to him as the ‘Son of God’. They recorded his words and sermons, believing them to be the words of God. The ‘Gospels’ became the foundation of today’s Christianity.

Muslims believe that the Prophet Mohammed recorded the words of Allah. Prophet Muhammad did not write them down. He was illiterate, according to several Islamic sources. The Angel Gabriel revealed the words of Allah to him over about 23 years (610-632 AD). Muhammad would recite these revelations to his followers, who wrote them down. These form the Quran.

The laws of Man have followed those attributed to God. It is a matter of faith whether one believes God wrote the rules. Nonetheless, rulers have called on their people to respect the laws of God for centuries. Indeed, many rulers believed that God blessed their ‘divine right’ to rule. What the ruler ordained must, therefore, by definition, be the will of God.

Cynics may say rulers chose what they wanted to do and used religion to justify it to the people. In 1534, did King Henry VIII of England sincerely believe that the English church would serve God better by separating from the Catholic church? Or was he upset because the Pope in Rome told him he could not marry the lady he wanted to? Either way, the effects on the English people and their laws and customs were profound and linger today.

Events mingling politics, social affairs and religion have occurred throughout history and still do. Urging troops into battle because ‘God is on our side’ is commonplace. Leaders of society also invoke God in subtler ways to exert influence.

Music

Songs, music, and verses play a large part in many religions. Hymns form a vital part of Christian religious music. One favourite for many in the UK is ‘All Creatures Great and Small’. Sung to rousing and cheerful music, the chorus after every verse goes:

All things bright and beautiful,

All creatures great and small,

All things wise and wonderful,

The Lord God made them all.

Most of its verses are similar, praising all the lovely things God has ‘given’ Man. Yet, buried in the second verse is this remarkable statement:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them, high and lowly,

And ordered their estate.

When the hymn is sung today, this verse is often omitted. It does not fit with today’s attempts at an egalitarian society. Yet, in Victorian England, the class system was established and accepted by most. Why did the writer need to include this sentiment in a hymn praising the earth's beauty and teeming life?

Cecil Frances Alexander, who wrote the hymn, was born in Dublin in 1818. She embodied the Victorian charitable tradition of helping the poor and disadvantaged. She knew what poverty entailed. This verse implies she accepted it as a regrettable but natural condition. But why refer to it in this hymn?

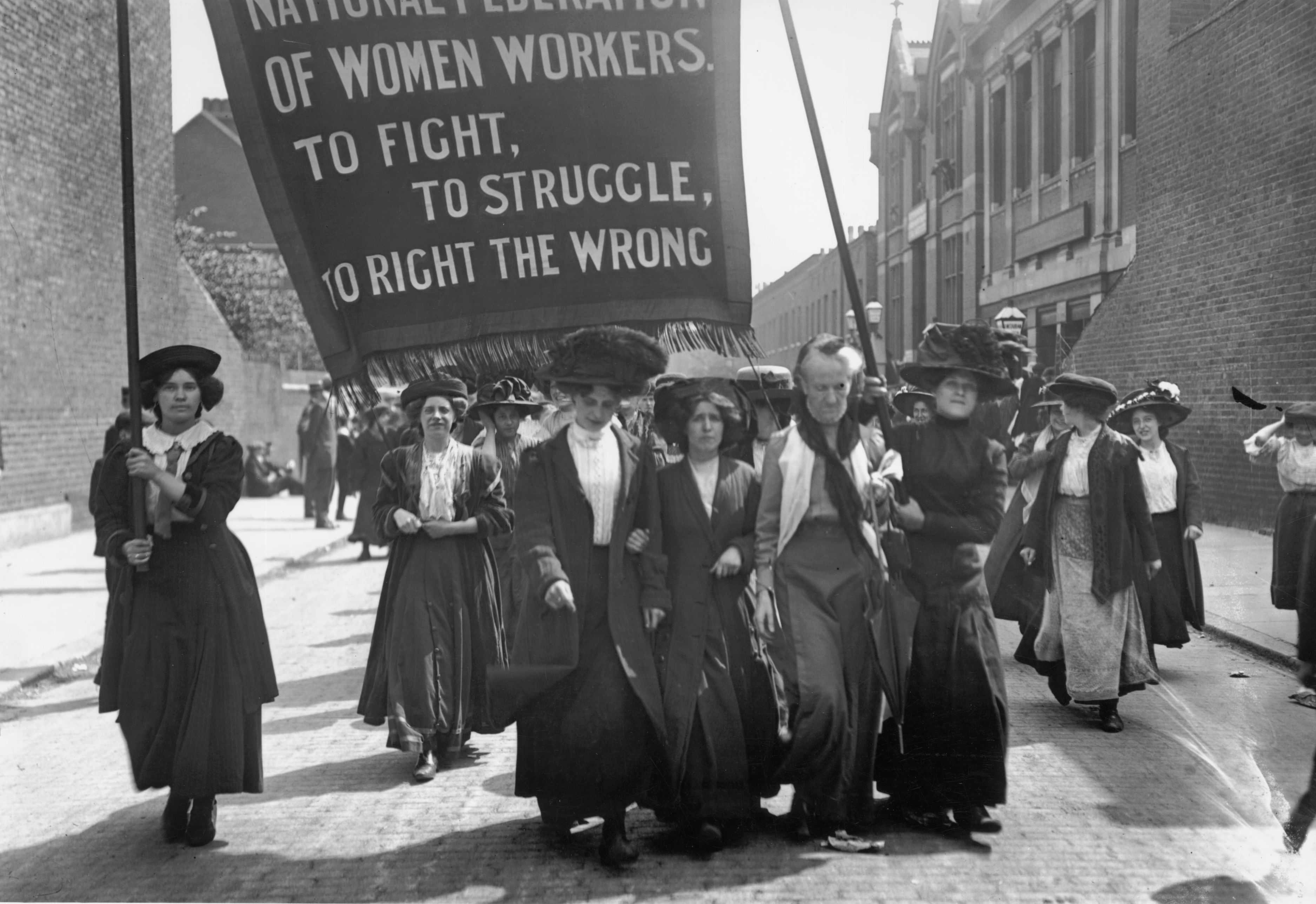

The clue lies in the date she wrote the hymn. She wrote ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ in 1848 – one of the most turbulent years in 19th-century European history. In February, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the Communist Manifesto. 1848 also saw struggles for more liberal governments, breaking out from Brazil to Hungary. Revolutions occurred, among others, in France, Sweden, Hungary, Germany, Romania, Serbia, and Sri Lanka. These significantly altered the social, political and philosophical landscape for the rest of the century.

To Ms Alexander, Victorian England's peaceful, ordered world seemed under grave threat. No wonder she wanted to remind churchgoers that only God ordained their place in life, rich or poor. Protests and revolutions were, therefore, challenges to the laws of God.

Faith is fungible

King Henry VIII’s Reformation of the English Church was traumatic for the people of England. Whatever some may have thought of the venality and corruption of Roman Catholic Bishops and Clergy, the Church’s beliefs, rituals, and practices had been revered for over 1,000 years. Many believed their immortal souls would suffer torment in Hell after death if they did not observe these traditional rituals. Their beliefs had to change profoundly within a few years to avoid prison or execution.

We now believe that ‘God’ made all human beings equal. Rich and poor are not ‘ordered’ by ‘Him’. (Women only received the full franchise to vote in the UK in 1928. But ‘God’ is still male.)

Homosexuality (illegal in the UK on religious grounds until 1967) only received the same status as heterosexuality in 2004. Only death or God could end a marriage in the UK until 1967. Even today, the Roman Catholic Church only accepts the end of a marriage under certain strict conditions.

Faith in a set of moral rules that a Higher Power determines is personal. In 1848, Ms Alexander may have believed that God chose a person’s societal position. I wonder if she would feel that today. Some sincerely believe their God’s laws are immutable and should never be changed.

Others call them bigots.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang