Population overload

The astronauts of the final Apollo space mission (17) took the 'Blue Marble' photograph 51 years ago in January 1972. It was the first taken of our globe as it looks in space and has become a source of wonder and hope for many people.

Earth viewed from space

The world population in 1972 was 3.84 billion.

Today, the world population is 8.1 billion. It has more than doubled in just 51 years. In my lifetime, the world population has quadrupled. Better health, prosperity, international trade, relative lack of pandemics, major wars, and lower infant mortality have led to this astonishingly rapid rise in the number of people on our planet.

What are the effects of this vast and rapid population increase on human beings? Environmental movements worldwide protest the impact we have on ecology. Famous locations now control tourism because there are so many more tourists. The roads are always crowded. Everyone seems under stress and irritable. Mental health has become an issue. Overpopulation affects our lives in many ways.

The effects of a far larger population on politics and national governance have received less attention.

Democracy

AI created protesters

Athens, where Western democracy began in the 5th century BCE, was a city of around 200,000 people. A common misconception is that every Athenian could vote for their government and participate in its decisions. However, only about 50,000 men could vote—the right to vote excluded women, slaves, and foreigners.

The democratic process evolved and is still doing so. Government "for the people by the people" has become a slogan for Western democracies. Colonial powers, including the USA, tried introducing democracy to former colonies before leaving them alone.

Today, liberal thinkers in many countries lament the rise of what they consider to be right-wing governments or government contenders. They believe that democracy is at risk when electorates choose strong leaders. Liberals are distressed because many countries want strong leadership. Liberals reassure themselves that citizens can replace a democratic government at least every four or five years. Thus, if a government pleases fewer citizens than it displeases, it will not stay in government for long. In more autocratic political systems, this may not happen.

Although each country differs, democracy has worked relatively well in most established democracies. Democratic thinking encourages creativity and innovation and permits many views and beliefs. Most democratic countries allow the right to complain, comment, and even suggest removing the regime. Yet most democratic countries' election systems mean less than 50% of citizens vote for any government. Furthermore, the number of anti-government protests globally has risen from 576 in 2006 to 1152 in 2020.

Democracy is in trouble, according to many experts.

What has changed?

For all its flaws, democracy has served societies relatively well so far. But when the population has doubled, individuals feel they have less voice. Neo-political and lobby groups, often representing relatively small numbers of people, feel they have the right to make their case. Each has their viewpoint and wants to reinforce it by whatever means. A government that wishes to remain in power (and which does not?) must somehow appeal to as many of these groups as possible to win the next election. Minority views sometimes prevail over those of the majority.

Communism in China

China has always had a large population in comparison to other countries. Allowing disparate groups to influence the government meant chaos, rebellion, and even warfare. Plato in Athens could afford to admire 'the chaos of democracy'. His contemporary, Confucius in China, demanded discipline, order and 'observance of the rituals'. With chaos, China's large population struggled with each other, effective government ceased, and people starved.

The Chinese Communist Party's aims for the country's people today are different, too. In his New Year message, President Xi Jinping stated, "China's ultimate goal is about delivering a better life for the people". On the other hand, Joe Biden hoped "that everybody has a healthy, happy and safe new year. But beyond that, I hope that they understand that we're in a better position than any country in the world to lead the world." Rishi Sunak lauded the achievements of his government and how he would improve the UK's economy.

Leaders from different political systems recognise that their country's people must be largely satisfied with government performance. How their government was chosen is less relevant.

What do the people want?

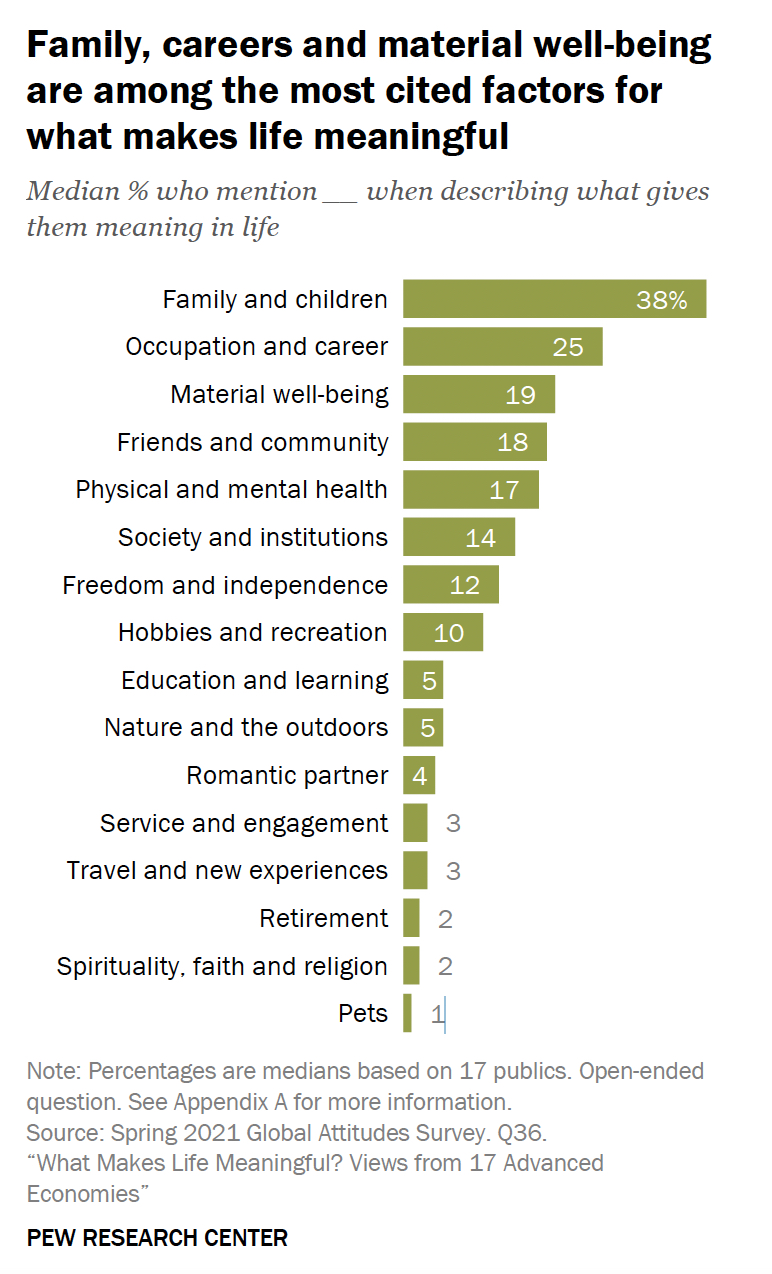

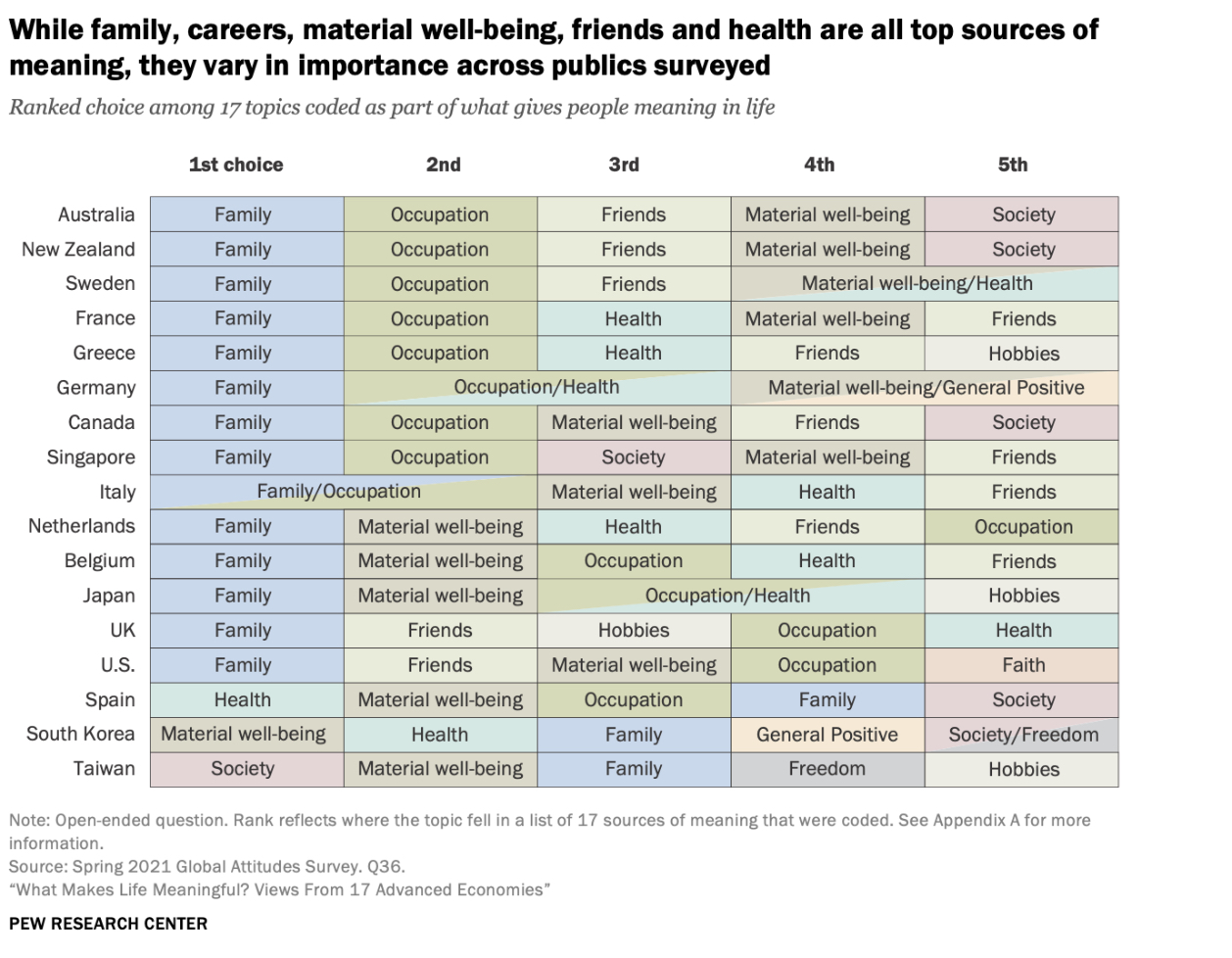

What do people value in life? How much of what satisfies people is fundamental and shared across cultures, and how much is unique to a given society? To understand these and other issues, the Pew Research Centre posed an open-ended question in 2021 about the meaning of life to nearly 19,000 adults across 17 advanced economies.

I notice that Freedom and Independence ranks 7th out of 16 factors. Most people are pragmatic. They choose family, health and material well-being above their desire to be free and independent. The priorities vary from country to country.

Only Taiwan and South Korea put freedom among their five priorities. But, even then, if it were to become a choice between family and material well-being, and freedom, most would choose family.

What would you choose?

What can democracies do?

One of the many inconsistencies humans exhibit is the capacity to behave differently in their public and private lives. I have frequently observed corporate leaders feel obliged to adopt behaviours they would deplore in themselves or their families. "This is business," they say, as if there are different standards between their business and private lives.

The same applies to politicians in democracies. They ignore reality by trying to satisfy everyone (so they may be re-elected). Their electors need stability and order to live the lives they want for themselves and their families. Political ideals may be important to intellectuals, the media, and academics. But they are just theories to most citizens.

With so many interest groups, all of which have points to make, democratic governments are losing their way in today's far more complex societies.

Conclusions

As populations grow, it becomes more difficult for democratic governments to satisfy every minority cause, however worthy. In any case, citizens are interested primarily in their own lives and success. This is why more of them are now choosing governments that may provide the discipline and order that a society needs to achieve its goals. As history tells us from Rome, Moscow, Paris and many others, everyone loses once order breaks down and civilisation collapses.

Democracy may still be the most humane and effective way to govern 7.8 billion people. But, as many others have written, democratic systems need reform and updating.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang