China – USA, a never-ending story

This week, we return to the rivalry between China and the USA. We examine the thoughts of well-known historians and commentators. We have written on this topic on several occasions too. ‘The Great Game..’ discussed the West’s automatic assumption that it had the right answers for the whole world. In “Bi-Polar world’, we examined the way in which western leaders use the media to further their political ends. ‘China and the World’ concludes that respectful rivalry between the USA and China is necessary and possible: angry rhetoric and trade wars harm everyone. This series of reviews continues with a summary of a few historians’ recent debate.

The debate

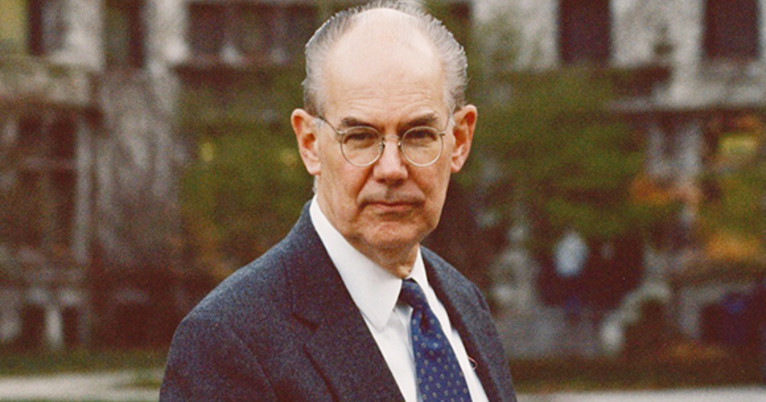

‘Foreign Affairs’ is a weekly publication produced by the Council on Foreign Relations in the USA. A recent edition contains a debate about the origins of the rivalry between the USA and China. Was USA right or wrong ever to have begun engagement with China. John J. Mearsheimer, a distinguished writer and historian, deplores the USA’s past efforts to engage with China.

Mearsheimer’s believes that the USA should have contained China’s rising power sooner. He criticises earlier US policy makers. They believed that China would become a liberal democracy like the USA, if economic growth took place and China’s population became more ‘middle-class’. With hindsight this was naïve.

G. John Ikenberry disagrees with Mearsheimer:

Even if this were to have been possible, doubts Ikenberry, the American public and the USA’s allies would not have supported it. However: “Mearsheimer is right that China presents a formidable challenge to the United States. The two countries are hegemonic rivals with antagonistic visions of world order. One wants to make the world safe for democracy; the other wants to make the world safe for autocracy. The United States believes—as it has for more than two centuries—that it is safer in a world where liberal democracies hold sway. China increasingly contests such a world, and therein lies the grand strategic rub. But in the face of this challenge, the United States would do well to work with its allies to strengthen liberal democracy and the global system that makes it safe—and to do so while looking for opportunities to work with its chief rival”.

Andre J Nathan (Professor of Political Science at Columbia University) also disagrees with Mearsheimer:

Nathan points to cultural, logistical, and geo-political factors that mean China is unlikely to be a long-term threat to the USA. Furthermore: “Mearsheimer is wrong to describe Beijing’s goal as global dominance. In a multipolar world, China will seek to shape global institutions to its advantage, just as major powers have always done. But it has no proposal for an alternative, Beijing-dominated set of institutions. It remains strongly committed to the global free-trade regime, as well as to the UN and that organization’s alphabet soup of agencies”.

Susan Thornton is a Senior Fellow at the Paul Tsai China Centre at Yale Law School. From 1991 to 2018, she was a career diplomat at the U.S. State Department, most recently serving as Acting Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. She writes: “I cannot agree that the U.S. policy of engaging China was a major strategic blunder. Engagement enabled massive economic growth in China that lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty—a significant reason that the share of people worldwide living in extreme poverty, by the World Bank’s definition, fell from 36 percent in 1990 to 12 percent in 2015. Surely, this counts as a major human achievement?”

After discounting the risks of war, she concludes: “China and the United States are not prisoners of history. The two countries will find that they cannot escape one another, and eventually, they will have to seek accommodation. This may now seem a distant vision, but it is a far more likely outcome, given the countervailing currents, than an apocalyptic war”.

Sun Zhe, Co-Director of the China Initiative at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University believes Mearsheimer’s views: “…rest on a misreading of what Beijing wants. In reality, China is in the midst of a process of soul-searching, with multiple perspectives inside the country on the future of U.S.-Chinese relations. China’s thinking is not monolithic, and its strategic direction is not preordained. Mearsheimer is wrong to see China as a growing hegemon whose only goal is to challenge the United States. Rather, China sees itself as a victim of bullying. As a rising, but not fully risen, power, it has by no means given up hopes of coexisting and even cooperating with the United States within the current international system”.

Mearsheimer’s ‘rebuttal’ acknowledges some of the points that the other writers made. Several times he alleges that ‘the facts’ do not support his critics’ views. He agrees that the USA/China rivalry may not lead to war but in any case, the USA has helped contribute to its own possible decline as a hegemon.

My conclusions

- Here are five eminent commentators and historians each of whom disagrees about what has happened and is happening in China and the USA. They are all based in the USA and, like it or not, live within the framework of western culture and values. They try to be objective. But they can never see events as a Chinese writer or historian would see them.

- Of the writers, only Susan Thornton has ever held a government position. Writers (this one included) sometimes forget that, in talking about ‘the USA’ or ‘China’ and their policies or views, these are an organic accumulation of opinions held by a wide range of individuals. ‘Chinese policy under Xi Jinping’ is no more the product of a single mind than a national decision taken in any western ‘democracy’.

- Facts are never absolute. What appears to be fact from afar, can be quite different close to. Journalists are fond of quoting facts to make a point. Regrettably, so are writers and historians. “I million people protested in the streets today” sounds impressive. But another way of expressing the same statistic would be: “Of the city’s population of 10 million, only 10% protested.” The impact on the reader is somewhat different.

- A key factor surely is this comment from Ikenberry: “the United States would do well to work with its allies to strengthen liberal democracy and the global system that makes it safe”. As we, along with many others, have observed – liberal democracy appears to be in disorder all too frequently. It is becoming harder, even for its advocates, to claim that it is the best system of governance for every culture in the world.

This will continue to be a topic for thought and occasionally headlines for some years. It behoves us all to listen to opinions from all sources before we form one of our own – if we ever can.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang