NEW BRAIN SCIENCE

Have you ever heard of Approche Neurocognitive et Comportementale (ANC)? No, I did not think so. You might be aware if you move in French-speaking circles or are in the field of human behavioural research. Even then, if you do not speak or read French, you would struggle.

I learnt about it from an online course I took from the Economist’s learning.ly. The lecturer was Gregory Caremans. Based in Belgium, Gregory is bi-lingual in English and French and has made it his life’s work to bring this new approach to the English-speaking world.

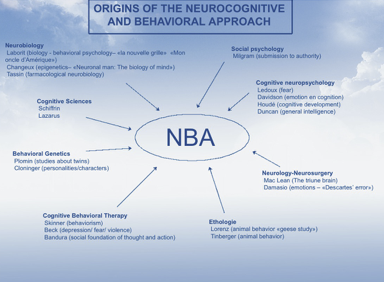

The ANC/NBA approach uses research from a wide range of complementary disciplines. It combines them to give powerful tools to help us understand our own and others’ behaviour. As the research continues, new discoveries emerge. As they do, the techniques will change too. The core to it all is the remarkable human brain.

The structure of our brain

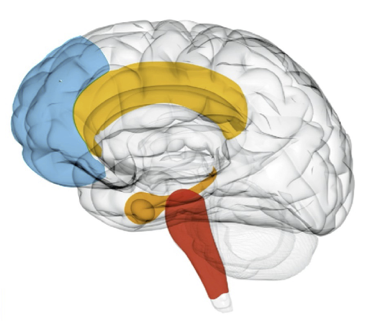

Scientists have plotted four sections in our brains.

The red part is the Reptilian Brain. This is our ‘animal’ brain. It gives us our immediate response to danger or fear. We have three options – to fight, to run or to freeze. It is essential to our survival sometimes – but that is all it does.

Immediately above it is the Limbic brain. This is the part that we develop as a child. It stores our childhood memories and experiences, the things we learned from our parents. Often, as adults, we do not know what is in there. And yet, these experiences shape the core part of our behaviours.

Above the Limbic brain is the Neo-Limbic brain. Here are stored the lessons we have learned from socialising with others. Here is where we adapt our core Limbic behaviours to suit our perceptions of social needs and approval.

At the front of our brains (blue in the diagram) is our Pre-Frontal brain. Here we analyse and think through our experiences. The Pre-Frontal brain is a super-computer. Although cats, dogs, apes and dolphins also have Pre-Frontal brains, the human Pre-Frontal brain is larger by far than any other species. It is what makes us human.

Each part of the brain is independent of the other parts. Yet they work together constantly.

How it all works

Let me give an example. You are leaving a bar after a couple of drinks – no more! As you leave, a large man bumps into you in what you see as a threatening and provocative way. What are you going to do about it?

In a flash, your Reptilian brain might urge you to fight back. You did nothing wrong. He needs to be taught a lesson!

Your Limbic brain – stored childhood experiences – is more confused. Fighting sometimes hurt as a child. You hesitate.

The Neo-Limbic brain – your socialised brain – may urge you to fight or it may urge you to do nothing. Or it may urge you to have a quiet word with the rude man. This will depend on your learning and culture. Whatever behaviour this part of the brain suggests, likely as not you will not be aware of why you chose it.

All this happens in your brain in milli-seconds. If you allow it to, the Pre-Frontal brain will take over. You may well decide that the man is far bigger than you: a fight is not worth it. It could be that you misinterpreted the event: it was just an accident as you were also going too fast. Or it could be that you noted a faint glance of apology from the man that you overlooked originally. You decide to ignore him, or apologise yourself, or smile.

This is a simple example of how the various parts of our brains work together. If they do not work together, we are stressed – quite literally struggling with ourselves. Counsellors and therapists will agree that stress is self-induced: we are responsible for our own feelings – not other people, nor events. Stress is in our minds. If the different parts of our brain are processing the same data in different ways, stress is inevitable.

Other facts

Our pre-frontal brain, the super-computer that helps makes sense of it all, is not fully developed until we are 24! Most of those younger than this do not have the capacity older people do to think things through or evaluate their different feelings and emotions to make rationale choices. Surely this explains a lot about our teenage children, youth protests and other behaviours that adults find worrying. (Note – adult Pre-Frontal brains will also tell us that the behaviours we sometimes criticise are not necessarily wrong, misjudged or malevolent.)

There are many scientists studying the brain. For all the advances they have made, our brain is still the least understood organ in the human body. Approche Neurocognitive et Comportementale is one of many techniques that help explain human behaviour. Some older people will say they have learned it all by experience.

Improving lives

Imagine how knowledge of this sort could help us at work! Employers say that the most difficult problems they face surround staff engagement and morale. Many employees say they find their job boring or their supervisor inadequate. They do not enjoy their work.

Some employers believe that paying staff more will help. It will not. The ‘good’ effect of a pay rise rarely lasts more than a very few months. Some employers in the ‘advanced’ Silicon Valley believe their sleeping pods, flexible hours, snacks-always-available, unlimited leave and other soft benefits show their humanity and make staff love them. There is growing evidence, though, that such staff feel their work and leisure time are mixed up – and it is not to their benefit. There was a lot to be said for a 9-5 job!

Suppose that we understood the root causes – what is going on in people’s brains, staff, supervisors, management, leadership? Can we somehow, using the approach here, help the whole team understand themselves and each other better? Work is, above all, a social activity.

Work occupies two-thirds of our lives. Improving how we see work and our colleagues must surely lead to significant improvement in everyone’s quality of life.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang