Politics and culture

Two aspects of society intrigue me. They are rarely linked together. One is Politics; the other is Culture. Note the Capitals. Humans have behaved politically for millennia to achieve their objectives. However, Politics – belief systems for the governance of societies – are new. Some define culture in terms of music, the arts and literature. However, academics have studied Culture – personal values, behaviours, and norms – only in the last few decades.

Culture

Politically correct dreamers maintain that there is no such thing as ‘national culture’. Even talking about it implies prejudice. Not all people in the same culture think alike, to be sure. But, if you grow up in one place, you will have the culture of that place. You cannot avoid it. Trying to pretend otherwise is to deny how human beings develop. That is not only naïve, it is also destructive: how can you understand anyone else if you are not aware of your values and beliefs, let alone theirs?

Geert Hofstede published “Culture’s Consequences” in 1980. It was the first study of how people in over 40 nations think and act – differently. He argues that people inherit mental programmes developed in early family life and reinforced in schools. These determine the values of the culture to which they belong. The latest brain research confirms that our Limbic and neo-Limbic brains reveal what we learned from the people who brought us up. Most of our values and behaviours we take for granted as ‘normal’. Few of us even know what they are.

Hofstede studied the beliefs and opinions of 117,000 workers in one firm in 66 countries in the late 1970’s. He called the company HERMES. It is an open secret that this was the biggest multinational corporation of the time – IBM. Using identical questionnaires in local languages, he identified four dimensions of culture:

Power Distance. This describes inequality between individuals and the extent to which they accept it. Consider the boss-subordinate relationship. Bosses try to increase the distance between them and their staff; subordinates try to reduce it. In society at large it is the same. Malaysia is high on Hofstede’s scale: Malaysians take power for granted and accept it from seniors. Austria is the lowest. Consider what that might mean for a Malaysian boss working in Austria – or vice versa.

Uncertainty avoidance. Life is uncertain. Coping mechanisms have existed since humans existed. Hofstede’s studies showed that tolerance of uncertainty varies across countries. Greece, for example, fears any kind of uncertainty. Singapore does not. The rules of each society are quite different because of that.

Individualism. This is the relationship between individuals and the collectivism of the society in which they live. “In some cultures, individualism is seen as a blessing and a source of well-being”, writes Hofstede. “In others it is seen as alienating.” The USA values individualism more any other country. Asian and south American countries value it the least.

Masculinity. The way in which different societies view the roles of men and women. Are men more assertive? Are women more nurturing? How does this affect their role in society? Japan had the highest masculinity score, Sweden the lowest.

(The Hofstede Institute – hofstede-insights.com – has taken his work further and offers useful tools for today’s international leaders.)

After Hofstede, others developed and expanded these concepts. In ‘Riding the waves of Culture’, published in 1998, Trompenaars and Hamden-Turner utilise the results from 30,000 questionnaires. They identify Rules .v. Relationships, Emotional/Unemotional, Nature, and attitudes towards Time as some additional criteria for assessing national culture. They also include nations such as China, that Hofstede could not.

In ‘Fish Can’t See Water’, published in 2013, Hammerich and Lewis identify national characteristics in some countries. These characteristics, they show, affect how national and international corporations operate.

The principles are the same in all the studies: each culture believes its norms to be correct and natural. All others are ‘foreign’ and suspect. The implications for global business and for individuals living and working in a ‘foreign’ culture are clear.

The facts apply equally to politicians, diplomats, and the media.

Politics

If ‘every country has the government it deserves’, national culture is the reason. As the world’s governments jostle for position, their leaders and media litter their practical struggles with emotional adjectives. This nation is ‘lazy’; that one is ‘perfidious’; those people are ‘disorganised’; this country is ‘aggressive’. Positive adjectives include ‘hard-working’, ‘cheerful’, ‘skilled’, ‘disciplined’. Words like ‘clever’ can be positive or negative.

Then there are the ways a national culture comments on others, foreign, culture. China is ‘despotic’; the USA is ‘violent’; the UK is ‘devious’; most states in south America are governed by ‘dictators. None of these descriptions is true. Officials and journalists use them to bolster their arguments.

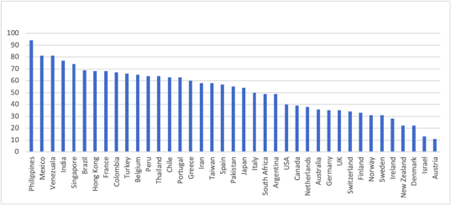

However, is that there is a direct link between national culture and the governance each country adopts. One chart, taken from Hofstede’s work, illustrates this well. This is Power Distance – the extent to which people accept authority. In the chart below, higher scores mean that the culture accepts authority more readily.

There are some notable absences. USSR and China are two. This is data from over 40 years ago. There are also one or two anomalies. And yes, my conclusions are simplistic.

But the nations that least accept authority are all western. They have chosen democratic governance systems that reflect their culture. Their governments have limited powers. The nations that accept more authority are mostly Asian and South American. Some are former colonies of western countries. Their governments tend to be led by ‘strongmen’; their authority is greater. We can see the differences from national reactions to COVID.

Were we able to view results from USSR and China, they would be close to, if not above, the nations that accept authority more readily. Their people are not only used to authority. As Hofstede points out: “many express a preference for a boss who decides autocratically or paternalistically.” My personal experience when managing or coaching people from China is the same.

With other dimensions of culture, chart after chart, the patterns are the same – clear divisions between North and South America and between Western and Asian countries.

Conclusions

National cultures may change – slowly. The Chinese culture was formed thousands of years ago. The culture of modern USA began with the first English settlers. European cultures owe much of their identity to the Romans and the Greeks. It seems likely that with more travel, the internet and 24-hour global news, national cultures will adapt faster than before.

The forces bringing human beings together are stronger than in the past. For now, though, and for the foreseeable future, we must accept that trying to change national values and beliefs will not be possible. There is yet no universally accepted value system to which all aspire. Each country will continue to decide its own Political future based on its culture and values.

At their peril do others intervene.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang