Where Silence Ends

Angela’s Great-Grandfather, Hector, was a macho, Mexican man. He had suffered macho abuse from his Father. He loved Angela’s Great-Grandmother and married her, virtually at the point of his own gun, in Mexico in 1926.

In 1952, their eldest son, also Hector, married Carmen, the girl who he had always loved and who loved him equally. In 1958, with one son, they moved to California. In 1961, their only daughter, Esperanza, was born. Three more boys followed. The family was stylish, well connected, and greatly admired.

Angela, the author if this book and Esperanza’s second child, was born in 1986. On a trip in 2013 to see the house where her Mother was born, she “could feel the tension mounting, vibrating out of my throat, chest, back, and toes.” From this point on, Angela’s account of the suffering of her beloved Mother becomes sinister, dark, and deeply disturbing.

Her Mother finally allowed her to read her journal.

I know my father started to molest me at a very young age, because at one point when I confronted my mother, she told me (this is so hard to write) that at age three, when she returned from her friends who cut her hair, she found me with a really bad vaginal rash. She said my father promised he would never do it again.

Incident followed incident throughout Esperanza’s early life and into her teens. Yet, while she was forced to live in the trauma her Father created, Esperanza’s brothers enjoyed the right to live outside of it. Hector was able to manipulate his own children into thinking life was normal, nothing was amiss, and everyone was happy. His sons believed that their sister lived in the same way.

Angela’s own Father (Ricardo) told her: “I knew your mom’s family for years before I asked her to be my girlfriend. Your Grandfather was always highly attentive and helpful. I never thought anything more than: ‘man, what a great family.’”

Angela writes:

I quickly came to understand that it was not enough to rely on a child to tell you if anyone ever touches them, even if you consistently ask them to tell you. As adults, we need to take the responsibility of diving deeper into these conversations with our children.

The more often Esperanza told the repulsive and barbaric truth about her relationship with her father, the more relief she felt. Her psychologist prompted her to begin her journal.

Years passed.

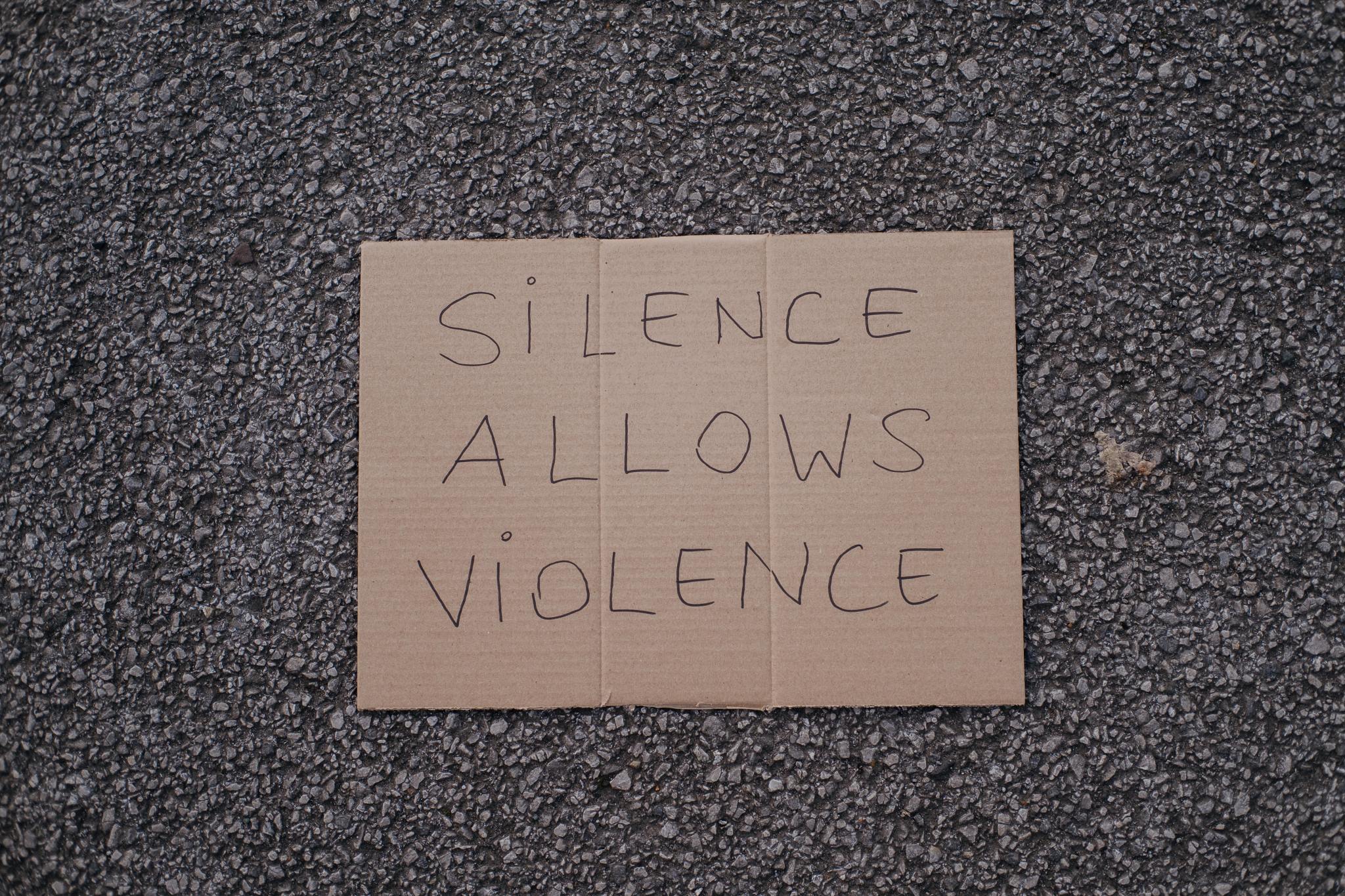

It turned out later that Esperanza was not Hector’s only childhood victim, nor the only one keeping a devastating secret. None of the women had shared their stories, even with one another, before Angela’s Mother mentioned her experience. Instead, the women let the pain fester and infect their lives, feeling alone in their silence for far too long.

Abused children go through many conversations in their heads, often convincing themselves the trauma they experienced was “not that bad.” But when an adult, decades older than you, touches you inappropriately as a child — even once — that is a crime, and justice should be served. When we shift the shame from victim to predator, we finally heal.

In this story, we clearly see that shame does not only live within victims, but also those close to the predator, including the predators’ enablers. Angela lays this out beautifully for us when touching on the relationship between her mother, Esperanza, and her grandmother, Carmen.

“Aren’t you going to say anything?!” Esperanza pleaded to her Mother. “What do you want me to say?” Carmen asked her daughter.

“Do you remember when you first realized he was touching me, mom?” Esperanza asked.

“Yes. It was when you were three. I took all of his clothes and put them into a suitcase for him, put it outside on the porch and told him to leave, but he would not.” Her tone was sad. “One does not want to remember everything that happened. These are terrible memories. You simply do not want to remember,” she said.

“But you are my Mother. You should have answered my questions honestly. You were not the only one who was hurt.”

“I know. It hurt the entire family, all my kids and grandkids, and others.”

Angela writes:

My Grandmother, Carmen, is an example of what happens when we allow dark to overcome light. I will take that lesson with me throughout life, allowing her errors to motivate me. For that, I am grateful. For that, I will always love her.

As society begins to understand sexual abuse and its prevalence, pushing it out from the shadows, we find ourselves wondering what we would do as a care giver or a victim. We like to believe we would speak up to save a child or ourselves. But the reality of trauma is never as clear-cut as you would expect, especially if you know the predator, as 80% of sexual assault victims do.

Angela writes:

There is a confusing mix of fear, shame, guilt, and paralysis, clouding one’s ability to protect even a child, let alone oneself. Unless you have survived horrors like my family has, you will never truly know how you would react to abuse and dehumanization. My hope is that you never have to find out, but if you do, I hope you prove yourself right — that you would speak up. Only Hector and Carmen are to blame in this scenario. They were the ones who chose to live a life of exploitation, intimidation and concealment.

Follow-up

Sexual trauma crosses all cultures, religions, economic classes, and countries. Many people have either been sexually assaulted or know someone who has been. Yet, as I have found, the subject remains taboo and closed off.

In 2020, in China, there were 332 cases of publicly reported cases of sexual assault of minors under the age of 14. These affected 845 children in China, according to ‘Girls Protection’, a charity focussed on sex education. The real number of cases is likely to be far higher. A series of proposals from Chinese lawmakers suggests that sexual assault prevention will be a priority for the government as it tries to overhaul how schools teach sex education. Every country in the world needs to pay more attention.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month. You should read Angela Ruiz’s book. We all need to know and to speak out.

Worked on the article:

Wanlikhang